This content is available to you for free thanks to the support of my Patreon’s generous supporters. If you enjoy it, please consider pledging to support future work.

EDISON: I thought we were doing worker placement games, next.

TEEL: November and December remain very stressful for me. I decided it was best not to try to write anything during November. Not after all those years of NaNoWriMo. Wouldn’t want to get myself started, then end up torturing myself over another unfinished novel. Started a massive fiber arts project, instead.

EDISON: Fiber arts? Is that what you’re calling it?

TEEL: That’s what it is.

EDISON: You’re crocheting a blanket.

TEEL: I think it’s going to be two blankets, actually. In my depression I seem to have made an error of scale. But I got through November and December without any suicide attempts, and I also managed to play more board games than ever before, so I definitely count those months as highly successful.

EDISON: And now it’s the first week of January, so instead of continuing our ongoing series of reviews by mechanic you’re having us write a top-ten listicle?

TEEL: Look around, Edison. This clearly isn’t in the listicle format. It’s our normal … Uhh… written podcast? Did we come up with a name for this, yet?

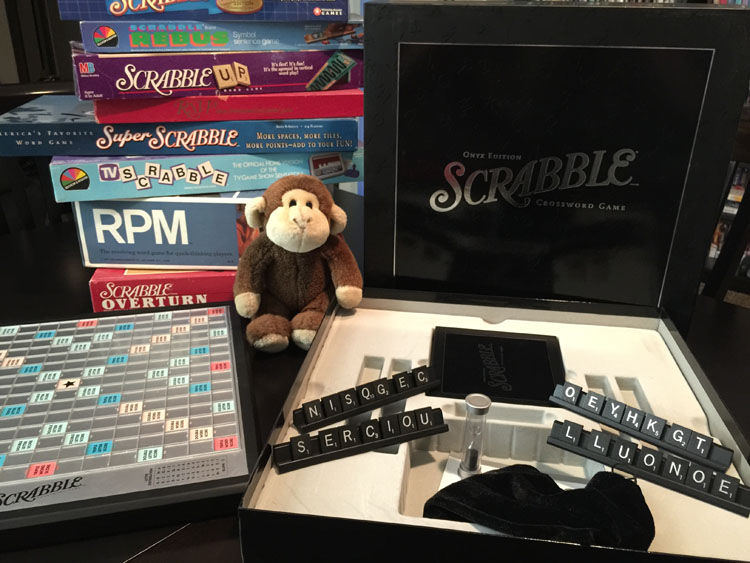

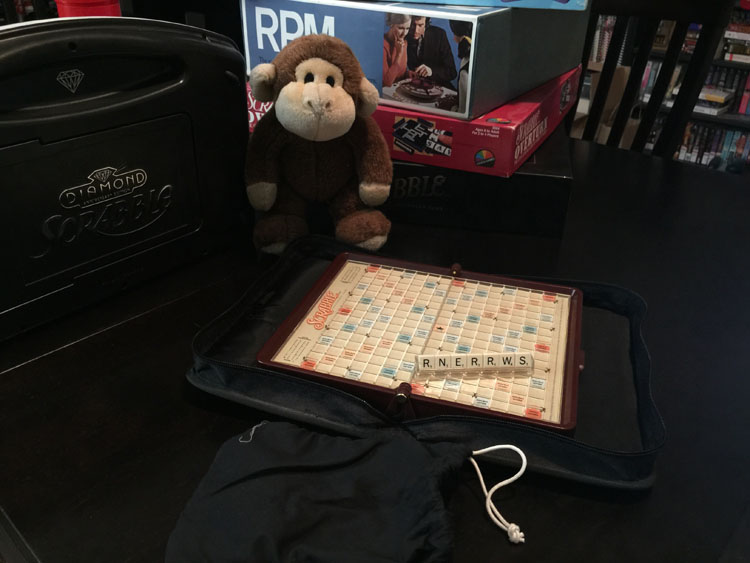

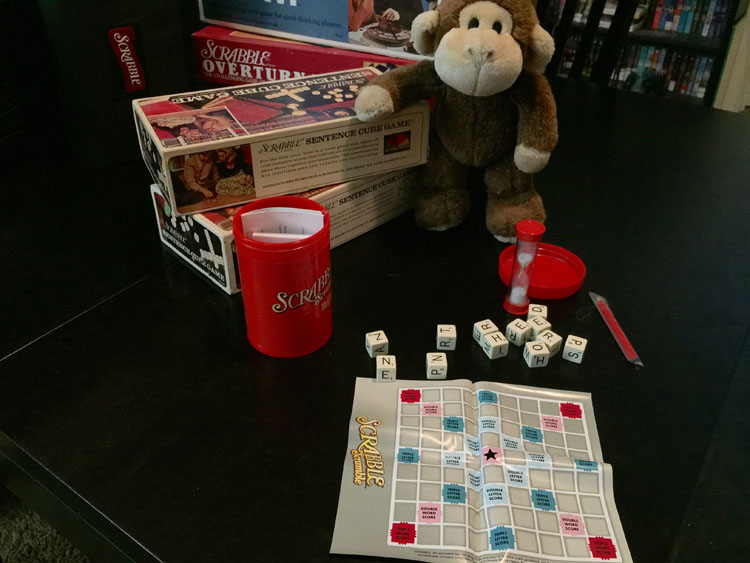

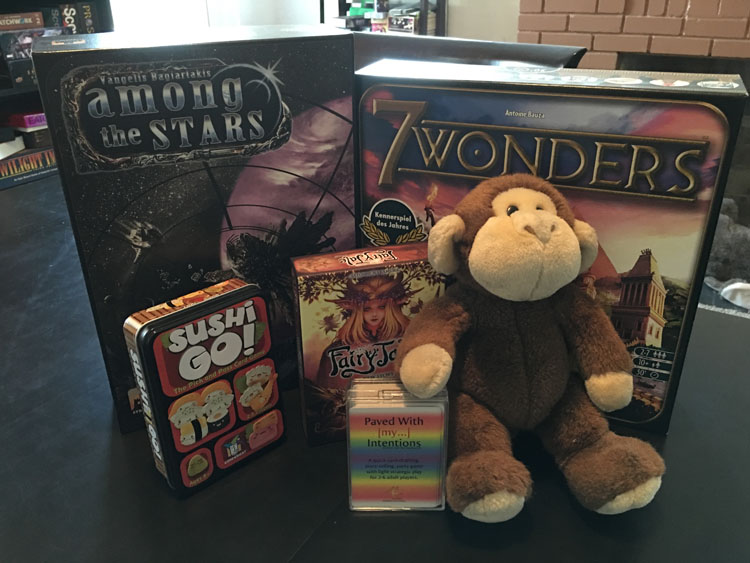

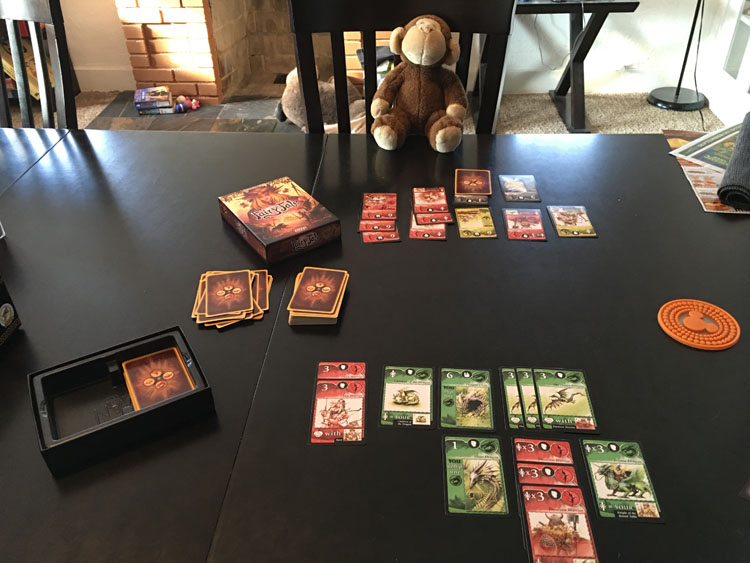

EDISON: Sadly, no. No established word exists to describe a grown man and a stuffed monkey discussing board games in the form of tens of thousands of words of written simulated dialogue interspersed with photographs.

TEEL: I’ll keep thinking about it. Content-wise, other than being written word rather than spoken word, it’s quite like a podcast on board games; maybe a further portmanteau from there.

EDISON: I don’t really think we need to coin a word for it. We only need to continue doing it as long as we wish to. So how did you want to begin? Do you have an ordered list, are we going through it backward in some poor simulacrum of Letterman’s Top Ten lists?

TEEL: What, because I’ve been so great at doing these things in an orderly and organized fashion so far, you think having a pre-defined format is a good idea?

EDISON: *shrug* Really I was hoping we could begin sometime soon, but didn’t want to be the one to bring up … the game I thought you’d have thrown out by now.

TEEL: I see. Because if we were going from worst to best in the semi-standard top-ten format I’d have to start with the game I hate the most.

EDISON: Which you’ve been ranting around the house about for weeks, and posting angry messages around the web since you finished it Monday, and generally making yourself miserable agonizing over—I was hoping you wouldn’t bring it to the table for this piece, since it’s supposed to be a “best of” thing.

TEEL: *sigh* But it’s winning almost everyone else’s “Best Game of the Year”, and the masses at BGG have managed to push it all the way to the number one highest-rated board game of all time spot, knocking out a game which has held number one for …I think eight years? Replaced by a game which had only been out for about 12 weeks. So my anomalous opinion deserves at least a little mention, don’t you think?

EDISON: You hated it. Can we move on, now?

TEEL: If we move on now, I’ll make you write an entire piece entirely about Pandemic Legacy, next week. We’ll get into every little detail of the mechanics, narrative, gameplay experience, marketing, and deeply into the culture of secrecy and praise surrounding the whole thing; it’ll easily be another ten thousand words.

EDISON: Please not that, Teel. I hated it almost as much as you, and I didn’t even have to play the game. Can you make it as short as possible?

TEEL: Well, since I don’t want to violate the modern-geek-culture religion of anti-spoilers right out of the gate (potentially keeping people from enjoying the rest of our conversation on the top games of 2015), here’s what I’ll say: I expected better. Better mechanics, better narrative, more interesting contents in all those little boxes, and overall I expected to have the Legacy mechanics improve upon the core gameplay and experience of playing Pandemic. I expected better, and because of the religion of anti-spoilers, everyone who knew what the experience actually contained created a culture of secrecy surrounding the actual content of the game, limiting themselves to (troll-like) simply hyping it as the best experience of the year/ever which one simply must experience for themselves.

TEEL: Unfortunately, the main conceit of the entire Legacy aspect of Pandemic Legacy was that a second, separate, unplayable and unwinnable version of Pandemic would play out on the same board you were trying to play Pandemic on—and if you couldn’t win your partial game of winnable-Pandemic before you lost the partial game of unwinnable-Pandemic, you lose. Sure, it changes over time, you get tools to slow down the rate at which unwinnable-Pandemic plays out and to keep unwinnable-Pandemic from replacing so much of winnable-Pandemic that it becomes equally unwinnable and eventually you get access to a little mini pick-up-and-deliver game which lets you further divide your experience into a growing third thing which amounts to a game of unloseable-Pandemic, but this is all at the expense of turns/actions you could have been using to play Pandemic.

TEEL: Right out of the box (this paragraph contains spoilers for people who don’t even want to know what’s visible after they open the box and before they play their first game; if you consider that a spoiler, I’m not sure why you haven’t already played your campaign of Pandemic Legacy) you get a sheet of stickers, about half of which are end-game upgrades—every game you play, win or lose, you may apply two upgrades to your game. Now, most of these you have to qualify for by doing different things during the game (e.g.: You can only put a character-upgrade sticker on a character which was actually played in the just-completed game.), but the majority of all the upgrades are “Positive Mutations” for the diseases. I bring this up because from the very beginning, before you even play your first game, this foreshadows the bleak future ahead of you: All the Positive Mutations have effects which reduce the amount of playing-Pandemic you actually have to do. And this is a slightly-bigger spoiler, but: By December, playing Pandemic isn’t even part of your stated objectives anymore; it becomes a few turns’ trifle while you work on what amounts to a combination of a simple pick-up-and-deliver game and a less-strategic version of Exploding Kittens; literally two of the least interesting game mechanics in modern board gaming, and they are the culmination of Pandemic Legacy’s gradual metamorphosis. Its final form: Boring, with a big helping of “no decisions necessary”.

TEEL: This is without getting into the trite plot, the obvious twists, and half a year of “your princess is in another castle” time-wasting mini-games in place of an interesting narrative. This is without getting into the mind-wrenching reaction I had after April’s first game, upon opening Box 3, and how inside I felt like Obi Wan shouting downhill at the disfigured form of Anakin, “You were the chosen one! They said you would [redacted for spoilers], not leave gaming in darkness!” By then I’d already been worried by the ever-worsening mechanics, but to be faced with that … my heart was broken. My hopes dashed.

TEEL: I won’t go so far as to say that it’s the worst game ever, or even the worst game I’ve ever played, but it is by far the most disappointing experience I’ve had in all of board gaming. I hate Pandemic Legacy, and I hate the culture of blind adoration and unbreakable secrecy which has so suddenly sprouted around it—without which I might have had more reasonable expectations about this utterly mediocre game. Rather than elevating an already-pretty-good game, the Legacy aspects of Pandemic Legacy ultimately drag it down into the realm of popular, shallow content which offers little more than what you bring to it on your own.

EDISON: …is that it, are you done ranting, now?

TEEL: *deep breath*

TEEL: Probably.

EDISON: Do you want to keep working worst-to-best?

TEEL: Not really. Largely because I don’t want to do an exhaustive list of every game I played for the first time in 2015, so the next game we’d talk about wouldn’t be anywhere near as bad as Pandemic Legacy, but by proximity and organizational structure it would come across that way to our readers. The next-worst game in the group is one of the ten-ish best games I played for the first time in 2015—and I played a little over a hundred different titles in 2015, most of them new-to-me. Pandemic Legacy was the worst experience by virtue of being the most disappointing, but the rest of this conversation will be about the cream of the crop. So let’s skip the the best, Mysterium:

EDISON: It’s basically Clue with Dixit cards, right?

TEEL: *sigh*

TEEL: No. Not really. There’s no roll-and-move, there’s very little deduction by elimination or logic, and it’s entirely cooperative. The only thing it has in common with Clue is that there’s been a murder, and players need to deduce the details of by whom, with what, and in what location the murder took place—the rest is quite original.

EDISON: I know, I know, I’ve seen you play it. It’s one of several games in this set which are at least partially asymmetrical, right? One person plays as the ghost, who knows the details of the crime & must communicate only via large cards covered in surreal artwork, and everyone else plays as psychics & must try to decipher the dream-like images they’ve been given into specific guesses about the crime. You and I can’t play it together because I know what you know and you know what I know.

TEEL: We could both be psychics.

EDISON: Sure, but then we’d need a ghost. A ghost willing to play with a stuffed monkey.

TEEL: Don’t tell me you’ve become shy! You used to be more social than I was.

EDISON: It honestly doesn’t take much to be more social than you, these days.

TEEL: Yeah, but you were more social than I was in some of my best days.

EDISON: And I haven’t left the house since I got here, have I? Now can we get back to talking about Mysterium? You’re saying here it’s your favorite new game, right? What makes it your favorite?

TEEL: It’s fun?

TEEL: I suppose it’s for part of the same reason Codenames works so well. What’s been done with the asynchronicity; one player in Mysterium, and one player per team in Codenames, is restricted to an extremely limited form of communication and then must sit silently while their teammates try to figure out what they meant. It creates a brain-burning good time on both sides of the table, as players talk each other into (and out of) various interpretations of the clues.

EDISON: So, like Charades. Or Monikers, which I notice isn’t on your list, but was on some others I read recently.

TEEL: I haven’t played Monikers. I don’t know anyone who owns it, and it doesn’t sound interesting enough on its own to me to buy. Similarly, I don’t play Charades and I’ve resisted buying any version of Dixit these many years.

EDISON: But you can see what I mean, right? If you’re saying what you like is the asymmetrical gameplay created by limited communication, how do Mysterium and Codenames, which are both on your best-games list, differ from old standards like Charades?

TEEL: Honestly, I’m not entirely certain. Maybe it’s to do with the limitations on the other side of the board. In Charades the clue could be literally anything in the world, and in Monikers it could be any person, and in games like Pictionary, Tellestrations, and Concept (which I haven’t tried, yet) it could be just about any word or phrase or concept in the realm of human thought. In Codenames you’re only possibly referring to the twenty-five words (or fewer, once guesses have been made) on the table and in Mysterium each player is only guessing from among a very small set of options—never more than six in games I’m played so far. So communication is limited, but the pool of answers is also very limited. It isn’t Twenty Questions, where you start with the entire world—you win or lose either game in at most seven or eight rounds of clues.

EDISON: I can also see how a more introverted, less social person would be more satisfied with a game where the giving of clues was less performative. In Charades the clue could be anything in the world and the way you communicate is limited to “all the ways the human body can be moved [which you are comfortable doing in front of a group of people]”; everyone is staring at you, and you must, effectively, dance for their pleasure. In Codenames you say only a word or a number, and then must only sit still and quiet while the rest of the gameplay takes place. In Mysterium you say nothing at all—have you considered the variant where you literally only knock yes or no, rather than telling people whether they guessed correctly?

TEEL: Yeah, actually. I think it could be fun.

EDISON: So you think, perhaps, that Charades would be a lot more fun if you could sit silently, hiding behind a screen the entire time, and when it was time for you to give the other players clues they didn’t look at you at all, instead focusing their attention upon the cards in front of them. Does that sound right?

TEEL: Actually, yeah. That’s not an unreasonable way to describe the being-the-ghost part of playing Mysterium, and being-the-ghost is definitely my favorite role to play. I’ve tried playing as a psychic a couple of times, now, though, and it’s pretty fun, too. Much more verbal, of course, but it’s like putting together a puzzle with friends—it still lacks the standing-up-and-being-stared-at-while-you-perform component to Charades and Monikers. I think I really like the puzzle of “How do these images connect to exactly one of these [suspects|places|things]?”, which is very similar on either side of the table.

EDISON: Do you have any complaints about either game?

TEEL: Other than not getting to play Mysterium as much as I’d like, so far? Probably the more-complicated systems for four or more players in Mysterium, where you vote on other players’ guesses and it tracks how well you guessed other people’s clues to determine how much of the final set of clues you’ll see—and then everyone votes on the final suspect, but if there isn’t a clear majority then it goes to the person who guessed other people’s clues better during the rest of the game. We’ve only actually used it once or twice so far, but it feels awfully clunky and complicated, and the bits for tracking your successful guesses are super-tiny and easy to bump. I’m considering looking up the other sets of end-game rules, or inventing my own.

EDISON: How many sets of rules are there?

TEEL: At least three: The English set I’ve got, plus the Polish rules and the Ukrainian rules. This part of the rules feels like it was added to make the game feel more game-y for American audiences. Voting and scoring tracks and giving some players a competitive advantage based on their earlier performance—it doesn’t sit right in a fully cooperative game. Coming to a consensus at the end (for the final guess) with more than two players seems to be tricky, so I’m at least going to try going to a secret vote next time, but if that doesn’t work I’ll be looking up the other sets of rules. I definitely love the rest of the game, even if the final round isn’t completely polished.

EDISON: And Codenames? It seems perfect for parties. Another one we can’t play alone, but have you tried it with two players?

TEEL: Not yet. I’m not sure it would be much good at four players, actually. I’ve tried it at five and it’s …okay? Maybe good, but also maybe only good because I was winning? My preference is definitely to bring it out at player counts of six or higher. It plays pretty great with eight people, and I expect it would be fun up through at least ten or twelve, though that might be pushing people’s ability to see all the word cards on the table.

EDISON: Twelve people is a fairly large crowd to get around a table, and they do appear to be mini-cards. But I suppose you could have lots of people filtering in and out between games—from what I’ve seen it seems to play pretty quickly and then get played again.

TEEL: Yeah, we usually play at least two or three games in a row. Depending on how distracted everyone at the table is with whatever else is going on at the party (and it’s definitely a party game) games can go anywhere from a few minutes to about twenty. They’re much shorter when someone accidentally chooses the assassin on the first turn.

EDISON: And is Codenames right at the top of your list, next to Mysterium, or are you presenting your top ten games in random order?

TEEL: So far? Pretty random. Mysterium is definitely my highest-rated new-to-me game in 2015, but I have six other games on my list in between Mysterium and Codenames. So… Last, first, and then eighth, I guess? Is that random?

EDISON: We’re clearly off to a good start. How random would you like to be next? Shall I roll a die?

TEEL: No, let’s confuse things further by going in logical order to number three on my list, Dungeon Petz.

EDISON: Logical order? What about number two?

TEEL: We’ll get to number two eventually. But Dungeon Petz is by the same designer as Codenames—Vlaada Chvátil. So it’s a natural transition, even though they were released years apart.

EDISON: I thought this was a 2015 list. When were Dungeon Petz and Codenames released?

TEEL: Technically, both were published for American distribution for the first time by CGE in 2015. Also technically, Dungeon Petz was first published in 2011. The former is only true because CGE used to work with Z-Man for North American distribution of their titles, but they took their own games back last year and put out new editions they distributed themselves.

EDISON: So why is a four-year-old game on your best-of-the-year list?

TEEL: Because I played it for the first time in 2015, of course! It’s a new-to-me-in-2015 list, not just a published-in-2015 list. Weirder than that, it’s the games which were new to me in 2015 but which I was also able to play enough times to form a solid opinion of by now. So games like Orléans, 504, The Bloody Inn, Trickerion, and Loop, Inc. (all of which were new in 2015, and show promise) probably won’t feature here because I was unable to get them played enough to rate and rank them before this week. Then when this time comes around again next year they still won’t feature because my records will show I played them before 2016—it’s a bit of a trap for some games, since I acquired a lot of new games in the last quarter of 2015.

EDISON: But you played a lot of games, too, right? Weren’t you saying you played more games in November and December than ever before?

TEEL: Yeah, that seems to be the case. I started tracking my plays on BGG back in mid-February 2014. I haven’t been 100% accurate with it (I seem to forget to log plays when it’s just Mandy and I at home and then we do something else afterward like watching TV) but I’ve tried, and it’s pretty close. With nearly two years of data, it looks like most months I play between 15 and 25 games, with one or two months lower (5 in July 2014, for some reason, or 6 in March 2015) and one or two months higher—prior to November 2015 my peak was playing 42 games in October 2014, and almost 15% of that was playing unpublished prototypes (which can be very quick games, if they’re broken). Then in November 2015 I played 44 games and in December it was 53 games, and less than a week into January I’ve already played 11.

EDISON: One hundred and eight games in about nine weeks seems pretty intense. Aren’t you worried you’ll burn out?

TEEL: Well, eighteen of those were Pandemic Legacy. But on the other hand, five of the ten-ish games on my list didn’t get here until the last quarter of 2015; playing my new games a lot has mostly been really awesome.

EDISON: I hope you continue to feel that way over the next few months. Now tell me about your number-three-for-2015, Dungeon Petz. It’s by the same designer as Codenames and has a bunch of really cutesy monsters on the cover—is it another silly party game?

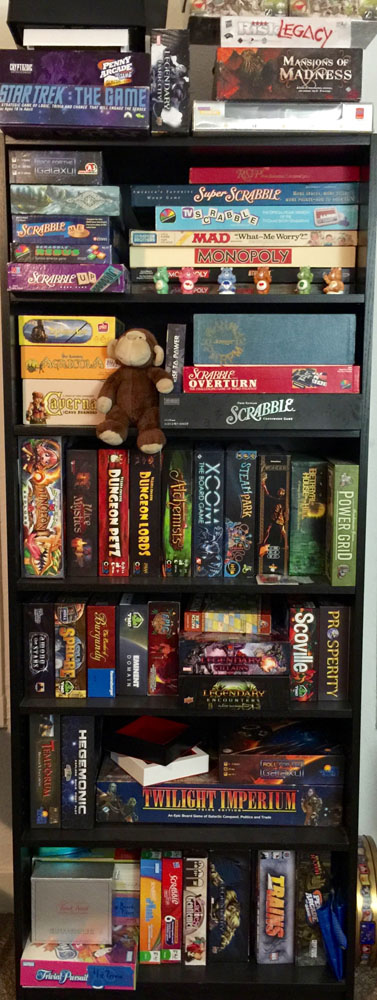

TEEL: Almost the opposite: It’s a heavy worker-placement game. In fact, along with its predecessor, Dungeon Lords (also by Vlaada), and Alchemists (which is right above Codenames on my list), you’ve got half the core of the Worker Placement games piece we were going to do. Agricola & Caverna are the other pillar games for that mechanic in my collection (though I have several others), but neither of those is even a little new.

EDISON: You’re doing an excellent job of keeping this thing organized. Shall we talk about Dungeon Petz, or are we going on a tangent to Alchemists first?

TEEL: Let’s talk about them both at the same time!

EDISON: These at least look like games I could play with you. Could we stop and play, first, or am I going to be little more than a foil for you again?

TEEL: We’ve already been at this for three hours, Edison. Each of those two games will take at least 90-120 minutes to play—and each actually contains at least part of the game which needs to remain secret from the other players, so while we could probably do okay at Dungeon Petz (the actual worker placement part would be tricky), Alchemists would be another impossible-to-effectively-solo-2p game. But do you really want to pause for a couple of hours to play Dungeon Petz, right now?

EDISON: It’s your number three game of the year, of course I want to play! I understand not wanting to try to play games requiring hidden information with me since I can see into your thoughts, though, so I’ll let it pass for now—as long as you promise to play it with someone else soon, so I can watch.

TEEL: That I can do… though we’re doing most of our gaming away from home, these days… I’ll try to get it to the table here, for you, or start bringing you to game nights. Something.

EDISON: I uhh… I think I can wait for you to play it here. You don’t need to take me out with you.

TEEL: It’s okay, Edison. I understand. You can definitely stay home until you’re comfortable and decide to go outside again. There’s absolutely no pressure.

EDISON: Thank you.

TEEL: So… Dungeon Petz is a follow-on to Dungeon Lords, where you played as a dungeon master, digging out their dungeon, hiring monsters to guard their treasure, hiring imps to do menial work, building rooms and defenses and accumulating treasure—and then the heroes would come “adventuring” their way into your dungeon, wreaking havoc, killing your monsters, stealing your treasure, and otherwise destroying your dungeon. (It’s pretty awesome.) In Dungeon Petz you play as a family of imps who decide to run a sort of “pet store”, except you’re raising baby monsters to sell to dungeon masters (presumably to guard their treasures in a game of Dungeon Lords!). Unlike Codenames, but like several Vlaada Chvátil games, you spend a lot of time building things up only to watch them be torn apart by the game despite your best efforts (see also: Dungeon Lords, Galaxy Trucker, et cetera)—in this case, trying to meet the needs of several growing monsters tends to wreak quite a bit of havoc.

EDISON: It sounds like you enjoy the havoc. Considering how poorly you react to things falling apart in your real life, I’d have thought you wouldn’t enjoy working hard to build something only to watch it be torn apart by forces beyond your influence.

TEEL: The difference is stakes. When I work hard to build something up in real life, it’s usually because it represents real value to me, and if it then comes crumbling down before me that represents a real loss, usually with significant real costs (in real money, and time, and sometimes in relationships, and psychological fortitude) coming due as a result of the destruction. In a board game there’s no real-world cost when my pet breaks free, or injures an imp, or mutates and grows an extra limb or two—it’s only a few points and maybe a win or a loss; in a game, for me, it’s very much about the journey rather than the result, but more importantly the results of a game have no ongoing effect on my life. In a board game, once everything is over, you just pack the game back up and put it away and you can have a fresh experience with it the next time you want to play. There are no real consequences, so only a fleeting emotional response to things falling apart.

TEEL: Plus, yeah, the monsters are cute and the idea of them competing in eating contests and being worth more to buyers based on things like how much they poop or how playful they are is silly and fun.

EDISON: Do you want to get into the worker placement aspects here, or are we going to write that piece someday?

TEEL: I haven’t decided. Probably. Maybe. I don’t know. But the worker placement part is also the reason why playing with you would be a little more difficult—in Dungeon Petz, you partially assign your workers in secret. You take your entire family of imps, however many you have on hand at the time, and you divide them into groups. Usually one or two or three, though I’ve seen groups as large as ten; you can also add gold to the groups to effectively increase the size of the group by one per gold. Then, starting with whoever has the starting player marker (which moves clockwise each round) and proceeding clockwise, but really starting with whoever currently has the largest group of imps+gold, each player takes one of their groups and places it (the whole group, spending any gold to the bank) on one of the worker places on the board. This continues in descending group size until all the groups are placed or passed—when it’s your turn you can always opt to keep your current group home to help take care of the pets you already control.

EDISON: So if I put my imps in two groups of three and you made three groups of two, I could get first dibs on the board for both my groups, but you would be able to take three spaces while I only took two? Or if I made six groups of one imp each I could do six things, but would have last pick of options?

TEEL: Not necessarily last pick, but close: Everyone who has any groups of size one would place one of those groups at a time, in clockwise order, until all those groups were placed or passed.

EDISON: I think I get it. So you have to guess how many imps other players will put in their largest groups if there’s something specific on the board you want to get, but if you guess too high you waste your imps and take fewer actions.

TEEL: Right, plus then your next-biggest group might not be able to get anything good, in addition to not having as many groups overall. It’s a pretty good worker-placement implementation, and the Dungeon Petz system of dummy imps to block spaces in the 2-player game works better than the player-controlled system in Dungeon Lords, I think.

EDISON: I haven’t played either, so I’ll have to take your word for it. Is Alchemists also by Vlaada Chvátil? Do you also build things up only to watch them fall apart?

TEEL: No, and no. But it is published by the same company, CGE, and has a thematically similar feel to the Dungeon Lords/Petz games. Plus, I think I read that Vlaada saw Alchemists and put the designer in touch with CGE which is how it got published… but I may have that wrong, so don’t quote me on that.

EDISON: Who would I quote you to? Also, isn’t this thing one big quote?

TEEL: Probably.

TEEL: Alchemists is a combination worker placement and logical deduction game, with a dash of bluffing thrown in. It’s played in combination with a smartphone app which tracks the alchemical properties of all the elements in the universe game. At the start of each game a new set of properties is randomly generated, everyone’s apps are synced to have the same secret set of properties, and during the course of the game part of what you’re trying to do is logically deduce the properties of the elements.

EDISON: Can I make a guess and say that people have claimed that the app-integration is gimmicky, and that you’re about to staunchly defend it as being a meaningful and useful addition to make the gameplay possible in ways which wouldn’t easily be possible otherwise?

TEEL: *nod*

EDISON: Can we skip that part and get back to what makes Alchemists fun? It’s, what, your seventh-favorite new game in the last year?

TEEL: BGG says it came out in 2014, but I think it wasn’t available in North America until 2015. Anyway, yeah, seventh on my list. It’s fun in part because the theme and the mechanics are so well-integrated. You can spend your morning foraging for toadstools and crows’ feet, then in the afternoon mix them together into a potion to try to discern their elemental breakdown—and you can either hire a student to drink your potion and see what it does (this gets more expensive if they’re given potions with negative effects) or you can guzzle it down yourself to avoid paying them (but risk your own bad outcome if it’s a paralyzing or insanity potion, for example). Once you begin to figure out which elements combine to make certain potions, you can sell potions to traveling heroes (probably going to raid the dungeons of the dungeon masters you sold monsters to, a bit ago). Once you begin to unravel the logical knot of the alchemical secrets of the universe, you can begin to publish papers with your claims—or bluff when you have only part of the formula, to get the grants and accolades that come with publishing, and hope you have time and knowledge enough to publish a quick retraction before the end of the game if you turn out to be wrong.

EDISON: It sounds richly thematic, but also brain-meltingly complicated and heavy. And you said it would take a couple hours to play?

TEEL: It depends. Mandy and I once finished in about 35 minutes, but with new players it’s definitely longer and if you don’t get lucky with the alchemical combinations it can be a real drag to logic out enough information to do anything useful. With all-new players, easily two hours. When I taught myself the game, solo/2p (which isn’t great, since each player’s deduction/logic data is secret, as well as their foraged components and whether they’re bluffing a publication or putting their name behind their work—knowing any of those things can give other players an advantage, if they’re clever), it took almost four hours; there was a lot of walking back and forth around the table.

EDISON: That’s quite a range of play-times.

TEEL: No worse than other worker placement games, like Caverna. I’ve played Caverna with only Mandy in about 20 minutes, and I’ve played a four-player game which dragged on for over four and a half hours, and I’ve played a five-player game that was done in about 150 minutes. It depends on the players, and on their knowledge of the game, but mostly on their AP.

EDISON: I suppose that’s reasonable. Would you say Dungeon Petz and Alchemists are the longest, heaviest games on your list?

TEEL: Probably? Aquasphere can be reasonably heavy, depending on how you play it. Maybe mid-weight. Why do you ask?

EDISON: They’re both highly thematic, and sound silly and light in that respect. So if these are the only two heavy games on your list, it seems that the entire list must favor lighter fare on the whole. Considering our earlier conversations about competitive gameplay, it seems like perhaps you’re developing a preference for light party games.

TEEL: Well, I’ve certainly made more of an effort to invest in smaller, lighter games this year—but only two or three of them made it to the list. The reason for the investment in games I don’t enjoy as much, and really I don’t like games to be too light, is a monthly game night Mandy and I have been hosting at a local pie shop. The tables there are physically small, and the people who usually show up aren’t board game hobbyists or serious players looking for a deep experience; it’s a light, easy-going social evening, with a side of games. Our collection now contains more than two dozen small-box, small-footprint games, most of which play quickly and are easy to learn. My preference is for heavier games, probably up to middle weight, or mid-heavy weight, but playing mid-light to light games is usually better than playing no games, or forcing someone to struggle through a game heavier than they’re comfortable with.

EDISON: So, let’s see… Based on box size I’m going to guess it’s Codenames, Entropy, and Burgle Bros.? Maybe Patchwork?

TEEL: Exactly. Let’s start with Patchwork, though, because I didn’t buy it for game night at the pie shop.

EDISON: Why not? Do your friends have something against quilting?

TEEL: Not that I know of, no, but it’s strictly a two-player game. We definitely try to lean toward 4-, 5-, and 6-player games at that game night, so everyone can get involved. No, Patchwork was designed by Uwe Rosenberg, creator of Agricola and Caverna, which are a couple of our favorite games; like Vlaada Chvátil and Stefan Feld, he’s a genius designer whose work I trust. So when I saw the rave reviews Patchwork was getting, and after watching Rahdo run through the gameplay, I started fighting against the fact that it sold out almost instantly every time it got re-stocked. Online stores sold out in hours. Local shops didn’t know when copies would arrive, or how many they’d receive, so they’d get one or two copies and they’d be gone the same day—and they don’t seem to be any good at taking pre-orders; when I secured my copy it was because I’d called the shop every day to see if it was there, was assured every time they’d set it aside for me, and on the day it arrived I went in and found “my” copy out on the shelves. If I hadn’t arrived within an hour or two of their shelving it, I might still be searching.

EDISON: Okay, so it was hard to get. How does it play?

TEEL: It’s great. It’s number two on the list, right behind Mysterium. The theme is fairly abstract—effectively you’re trying to efficiently arrange Tetris-like pieces into a grid, and managing two currencies (buttons as money, and time as progress along a limited track) to try to control which pieces you and your opponent will have access to throughout the game. During end-game scoring you lose points for un-filled spaces on your board, so it’s not unusual for one or both players to end up with a negative score—but highest score still wins. All these little pieces come together in such a way that almost every decision you make will be interesting and engaging, from which pieces to buy (not just to fit into the puzzle you’re building, but to plan ahead multiple turns & guess what your opponent will want) to how to fit them into your board and whether to try to strive for the patches (single-square pieces, for filling in holes) and/or the 7×7 award (filling in a complete 7×7 square turns out to be surprisingly challenging!) or simply to avoid working yourself into an impossible corner. Or four.

EDISON: So it sounds like it’s relatively light, but without sacrificing the mentally-engaging, puzzle-solving goodness of heavier-weight games. Does it play quickly?

TEEL: I’ve never timed it, but it feels quick, for certain. It definitely doesn’t overstay it’s welcome, and one often reaches the end of the progress/time track wishing for a couple more actions. I wouldn’t usually say it’s true, but sometimes that’s exactly the right time for a game to end—just a little bit before you’re entirely satisfied; leaving you wanting more.

EDISON: Isn’t that the opposite of what you were saying in our piece on deck-building games? Especially after we played Eminent Domain? That games often end too soon, before you really feel you have a chance to carry out your plans?

TEEL: True. Maybe it has something to do with a feeling of agency. In Patchwork, the other player could rush a little bit ahead under the right circumstances, finishing the game while you still wanted another couple of pieces—but because of the way turn-order and end-game are handled, you don’t actually have to stop playing just because they reached the end of the track. In Eminent Domain, especially with those infinite-VP technologies in play, the game can end instantly because of something at least out of your hands and possibly out of your sight. You’re rolling along, building your empire, when suddenly, “BAM!”, the game is over. This is different from games like Patchwork, The Bloody Inn (which we only started playing this week), Dungeon Petz, Alchemists, Mysterium, or Above and Below, where there’s a pre-defined timer built into the game and visible to all players—you feel the clock counting down, and maybe you wish you could have done a little more, but you’re never taken by surprise when the game suddenly runs out.

EDISON: It sounds like you’re bothered by a loss of agency; that you don’t like the end of the game being potentially a surprise and in the hands of another player or a randomizer.

TEEL: That could be right. I was definitely frustrated with the game of 504 we played recently where there was a potentially-12-turn progress track made out of randomized cards in such a way that one of the last four cards would instantly end the game. If it had been the first of the four, three turns would have been left out of the game—that’s a full quarter of potential gameplay. If it had been the first or third of the four, one player would have had fewer turns than the other. It felt really awful and agonizing to try to deal with, and made planning for future-potential-turns almost pointless but also potentially vital to winning.

EDISON: That was definitely less than ideal. I know we’re only 4 games into the 504 possible games in the set, but I’m already worried that the majority of the games in 504 will have at least one dull, broken, or frustrating aspect, based on what we’ve seen so far. How many different games of 504 do you think we’ll get through before you give up on it? Do you suppose you’ll ever find one you like enough to play more than once?

TEEL: I’m dedicated to playing at least nine games, to systematically try every module in every position. Then maybe, based on our experiences with that, I’ll try to come up with some combinations I think will actually be more fun than what we’ve seen so far. As far as repeating a world … I don’t know whether I’ll continue to prefer seeing new worlds over repeating old ones; it would have to be a shockingly-better-than-average game of 504 to really stand out as needing repetition, from what I’ve seen—and I’ve read all the rules, already.

EDISON: I know you were really excited about it from a game design perspective, and bought it without really looking into what the gameplay was like, but–

TEEL: Not only that, but reviews are thin on the ground for 504; since the experience space is so vast, most reviewers don’t seem to have much of value to say. They either stick to their normal tactic of reviewing a game after only one or two plays through, which means not seeing the vast majority of what 504 has to offer before pronouncing their verdict, or they’re gradually working through (at least) the minimum nine games to see every module in every position before really trying to form an opinion.

EDISON: Which I think is what you’re doing, right? Is that why you put it all the way in the back? It isn’t really on the list, yet, is it?

TEEL: Not really, no. I’m not sure what I’ll end up rating it, overall. The four games/worlds we’ve tried so far wouldn’t rate high enough to make the list, for sure, but the overall concept is so intriguing.

EDISON: That gets back to what I was trying to say before you interrupted me: You bought it without looking into the gameplay, but it’s turned out the be quite dry, hasn’t it? So far the rules and mechanics are really only about middle-weight or light-mid-weight, but the themes are dry, dry, dry. No cute or silly monsters or surreal artwork or wacky potion-mixing to be found. The whole thing is barely above an abstract. I don’t see how it fits into your collection.

TEEL: Well, I had a hint it would be a dry euro-style game; it’s designed by Friedemann Friese, creator of such dry, mathematical exercises as Power Grid. Which I own, and which I like okay, but which never seems to make it to the table—there are too many other games in my collection I want to play a little more. Even something as dry and abstract as Prosperity has enough interesting theme to elevate it above Power Grid, for me. I guess I really love thematic games.

EDISON: But not too thematic. You don’t exactly have shelves overflowing with Ameritrash, Teel. I’d say you liked games with a good balance of theme and mechanics, with a slight preference toward heavier, more thought-provoking gameplay.

TEEL: Sure, and 504 provokes my thoughts in spades! Unfortunately, at least half that provocation is about the meta; thinking about how the modules work together, understanding how the rules can be generic enough to be compatible with any other set of rules but also unique enough to bring something original to each different world they’re a part of, and then dissecting how the games actually played, after the fact, to try to learn something about game design. Obviously the games have been long and complex and have been generally full of interesting decisions; you played them with me, you know. But I’m not sure playing 504 is the best part of owning 504.

EDISON: So it’s one of the most interesting, if not one of the best, games of 2015, then?

TEEL: That sounds about right. If I were doing a top-ten-ish most interesting games of 2015, both 504 and Pandemic Legacy would certainly be on the list, even though they probably don’t deserve to be on any “best games” or “most fun to play” lists. 504 is the sort of game I want to keep playing, but not necessarily because I enjoy playing it more than other games. It’s more that I enjoy thinking about and working through its iterations quite a bit, and playing it is the best way to really grasp how the pieces fit together.

EDISON: Which I guess brings us back around to Patchwork, a game which is actually supposed to be on this list. Did you have anything else to say about it?

TEEL: Not really. It’s quite fun, I enjoy playing it, and I look forward to playing it more in the future.

EDISON: Alright, so now we’ve covered the top three games on your list, two games not on your list, and the seventh and eighth games on your list. Where do you want to go next?

TEEL: I’m thinking we go to number four on the list, Roll For the Galaxy.

EDISON: That almost sounds logical, since we’ve already covered one through three.

TEEL: You might think so, but really it’s because the other five games on the list have something in common. Roll For the Galaxy is the only game left on the list which didn’t reach me via a Kickstarter campaign.

EDISON: Interesting. Is there anything else in common among the other games? Publisher, designer, or the like?

TEEL: Two of them are from TMG, I suppose. Not really. We’ll get to that, though. Let’s dig into Roll For the Galaxy.

EDISON: I’m surprised you’re the one trying to keep us on task, for once.

TEEL: It may not last. But let’s take advantage of it while it does. Roll For the Galaxy is a sort of dice-based adaptation of an earlier, very popular card game called Race For the Galaxy. Roll For the Galaxy came out in December 2014, but it was in short supply (as was my budget at the time) so I wasn’t able to play it until 2015—and I put off buying my own copy for most of the year, because one of the people at a game night I attended every week brought their copy with them every week. When that game night got shut down, I immediately ordered my own copy of the game. Soon I’ll order the expansion that recently came out, too.

EDISON: You must really have liked it. Why isn’t it any higher on the list?

TEEL: The game is not without its shortcomings. For example, the end of the game is triggered either by the pool of VP tokens running out or any player constructing their 12th thing (planets & developments)—so it’s got that same problem where you can be head-down, working on your own little empire, when all of a sudden another player instantly triggers the end of the game.

EDISON: Can’t you see it coming, though? Everything they build is out in the open.

TEEL: But dice play a big role in the success of any given turn, too: It’s entirely possible for someone to be struggling to build their next thing for turn after turn because of bad rolls, then suddenly settle two or three planets in a single round, ending the game. There’s a little balance, in that the planets and developments you can build with fewer dice are worth equally lower VP at the end of the game, but there are 6-point developments which can make building a lot of cheaper things worth a lot of points at the end of the game—especially if you can trigger the end of the game before anyone else is ready. Depending on how the dice go for me, and which tiles I pull at random from the bag, Roll For the Galaxy can either feel extremely good, where I’m building a great little synergistic galactic empire with thematic elements that make sense together, or it can feel like I’m racing against another player or two, fighting against a pool of bad dice and bad draws, and the game ends at least half a dozen turns too soon.

EDISON: So it’s wildly uneven.

TEEL: Yes. But each game plays relatively quickly. In an experienced group without bad AP, an entire game (both 2p and 4p-5p) can be over in 20-30 minutes. They don’t even necessarily need to be experienced with Roll For the Galaxy, only to be experienced with board games in general. It’s one of the few games I’ll readily play another game of immediately after finishing a game; normally I prefer to move on to something new, but even two or three games of Roll For the Galaxy in a row are light and quick enough that, like Codenames, I don’t feel … the slog. A lot of games, if you start them again, feel like the game has simply continued; like the game wasn’t a few turns too long, but an entire game’s worth of turns too long. Roll For the Galaxy doesn’t usually feel that way. At least not for the first couple of games.

EDISON: So tell me more about how it plays. You said there are dice?

TEEL: Oh, yes, lots of dice. So many little dice in all the colors, and noisy little dice cups, and it’s wonderful. You start with basic dice and depending on how you expand your space empire you add more and different sorts of dice to your pool, which have different odds of giving specific outcomes. Typically, the more specialized you’re able to be, the better. You roll the dice at the start of each turn and which symbols come up determines what actions you’ll be able to take that turn—you always specify one sort of action to definitely occur (and don’t even need a matching die for that action), but you want to pay attention to what other people are doing because any actions not selected by any players as their definite action do not occur that round. So you might roll a whole mess of dice that come up “Settle a planet”, but if no one chooses the “Settle a planet” action, you don’t get to use any of those dice; you either want to force it yourself, or if you know someone else will be settling, you can force one of the other actions which will give you another benefit—like if you’ll be able to settle a planet which starts with goods on it, ready to ship, you may want to force the “Ship goods” action to immediately get some extra cash (or VP tokens).

EDISON: And you’re saying AP isn’t a big problem in this game? Wouldn’t players spend a lot of time trying to figure out what everyone else is doing, or trying to optimize their actions so they don’t waste dice?

TEEL: There’s a lot of luck-mitigation available in Roll For the Galaxy; you can build developments which let you “Reassign” dice, using them for actions they didn’t come up with, and any dice you’re entirely unable to use (say, because the action didn’t occur that round) go directly back into your dice cup rather than to your dice pool (where you have to pay currency to get them back into your cup), and you always get at least one die in your cup—which you can choose any action with, since the die you use to force one of the actions doesn’t have to match; in the worst-case scenario where you end a turn with no money and no dice in your cup, you know for certain you’ll be able to do at least one action, any action, of your choice on the next round. So while it can be worth it to try to figure things out to the last detail, mostly you’ll be okay simply working with whatever you rolled—and being thoughtful when choosing dice for the next roll. My general philosophy of gaming, these days, is to be very easy-going and friendly, and that’s also the sort of people I like to play games with. As a result, everything tends to be a bit more laid back, especially with a game as brief as Roll For the Galaxy.

EDISON: I suppose that’s probably good for your mental health. You don’t find it limits your gaming experiences too much?

TEEL: Honestly, I’ve been working more in the last couple of months to cut undesirable gaming experiences out; this is, of course, exacerbated by the eighteen games of Pandemic Legacy I played across December and the first few days of January. As you can imagine, I don’t want to repeat that sort of forced march. I went through a similar thing with Tiny Epic Defenders earlier in the year; I kept thinking, “maybe I’ll like it better next time, or with different players, or on a different difficulty level”, but it never got any better. Along those lines, I’ve begun (perhaps too vocally, at first) to refuse to play hidden traitor games and bluffing games and really anything in the class of games built around lying to one another. Secrets and lies are not elements I want intentionally to be adding to my life.

EDISON: Even when you know it’s only a game? What about role-playing; couldn’t you put yourself into the character of someone who would lie in the scenario presented in the game?

TEEL: I’ve never been much of an actor or role-player. In high school I spent a little time on the stage, but effectively ended up playing different versions of myself. In at least two instances, plays were re-written to turn whatever character (or characters) had been there before into someone more like Teel. I never asked for it. I’m not sure I ever even auditioned after the first time went so poorly—I didn’t get the part, but a few weeks later they’d added me into the play, anyway. And that kept happening.

EDISON: You’re very odd. You know that, right? What you’re saying right now is very odd.

TEEL: I know. It’s just to say: No, it isn’t merely a game, and no, I can’t be someone else. When I try, my brain and my heart tend to break in particularly terrible ways. In the past, I’ve given in and played along when the whole group wanted to play something like The Resistance, or Coup, or any version of Werewolf—anything like that. Now I’m trying to avoid playing the games I don’t want to play. Sit it out. Spend the time staring at my smartphone, or thinking about anything, or nothing at all. Starting up a parallel game with anyone else who didn’t want to play. It’s been a little rough; I apparently get explicit in my hatred, at times, which unnerves people; I’m working on it.

EDISON: Helps to have such a large collection of games you do want to play though, I suppose. Which one shall we talk about, next?

TEEL: There we are, back to the old ways. Yes, fine, keep me on task. Let’s see… is there a logical order to go through the rest of these games?

EDISON: Continue from top to bottom, perhaps, skipping those we’ve already discussed? What’s your number five game?

TEEL: *sigh* Fine. You’re so un-creative. It’s Above and Below. My first game by Ryan Laukat of Red Raven Games, it’s given me an urge to buy several other Red Raven games—but they seem to run expensive, go out of print quickly (if you miss their Kickstarters), and I’m so far behind now that it would take a veritable fortune to get my hands on the games I’ve missed. Which, strangely, I believe indicates I may never buy another Red Raven game; I can’t really afford to be a proper collector, but I also wouldn’t want an incomplete collection.

EDISON: Is there something in particular you enjoyed about Above and Below which makes you wish you could collect all the games by the same designer? Is it the artwork, or the mechanics, or some silly thing about the theme and mechanics integrating particularly well?

TEEL: Come to think of it, the theme and mechanics are pretty abstracted from one another. There are mechanics for constructing buildings in your village, but you’re basically just buying cards to get passive bonuses. There are mechanics for training up villagers to work for you, but you’re basically buying action flexibility for future turns—and the number of actions you can take only really goes up if you build the right buildings; it isn’t based on the number of villagers you’ve trained. There’s a very distracting set of mechanics for sending your villagers of little CYOA-style explorations (usually with one “choice” each), but it comes down to using half or more of your available actions to roll some dice to maybe get some goods. You can mitigate the luck involved by training villagers who are better at exploring and by sending more villagers (using up more of your available actions each round), but it isn’t as though the villagers have any explicit stories about who they are and why they’re any better at completing a random story/exploration than another.

EDISON: It almost sounds like you don’t like this one, Teel. Are you certain it’s in your top five games of the year?

TEEL: I do like it. I was just explaining that, unlike games like Dungeon Petz/Lords, Alchemists, or even Mysterium, where the theme and mechanics are particularly well integrated, Above and Below has theme, and it has mechanics, but they run almost entirely parallel to one another. I’ve heard (and seen, in Rahdo’s run-throughs) that the same is true of Ryan Laukat’s other games, such as City of Iron and Islebound (both of which I wish I’d been able to afford last year), but it’s not a deal-breaker for me, at all.

EDISON: Why not? What makes Above and Below different from, say, 504?

TEEL: 504 has only the thinnest veneer of theme applied to any given world. Ryan Laukat’s games take place in a rich, engaging world full of interesting people, species, locations, and cultures—all depicted in Ryan Laukat’s original (and breathtaking) artwork. In Above and Below in particular, when you send your villagers on adventures (when they explore), one of the other players reads a little story to you about what they come across on their adventure, and gives you a choice about what they should try to do next; this adds significant depth, over the course of several games as you explore more and more of the world, to the world of the games. Though honestly, I think I’m won over first by the artwork and second by the interesting mechanics; I’d like looking at the gorgeous artwork of Above and Below even without any flavor text or mini-stories to give it background and depth.

EDISON: It looks like Above and Below is almost entirely language-independent, except for the book full of stories. None of the villagers or locations have names, there’s no flavor text, no backgrounds, it’s all just beautiful images and the icons used for playing the game.

TEEL: That’s correct, but if you look at something like Dungeon Petz you’ll see the same thing—and there’s no shortage of story communicated by those images. I admit that the Dungeon Petz manual does name all the monsters, events, and dungeon masters and gives them a little story, a little background, a little flavor text—but you could figure most of it out from the artwork and the icons. To a lesser extent, the same is true for Above and Below.

EDISON: Which I suppose explains why it’s a couple places lower on your list, right? At least in part?

TEEL: At least in part, yes. It can be fun to try to make up stories about the different villagers, or to guess how the different buildings might be to be able to provide the bonuses they do, but I certainly wouldn’t turn down an explanation from the creator of all those people and places about what’s really going on.

EDISON: Not being a role-player, you like to have your stories handed to you, rather than having to make them up yourself, on the fly.

TEEL: Yes and no. I’m an author and a storyteller, and I can be quite creative and verbose—but I also respect the work and imagination of other creators. Coming up with a dozen stories to explain what the ghost in Mysterium might have meant by the dreams/visions they gave you is no problem, and since we’re left at a loss I also tend to make up stories about the villagers in my employ during Above and Below, but if Ryan sent me a PDF with as little as a one-sentence description and name for each villager token, the entire game would become instantly more rich and vibrant—and a better jumping-off place for inventing ever more new stories about their ongoing experiences. Maybe knowing a particular explorer’s background would make it easier to imagine what they would do when faced with a specific situation from the book, making it more an exercise in role-playing than in trying to optimize to get the most goods per explore action. It’s difficult to say.

TEEL: What I can say is this: Above and Below is fun to play. It provides more than enough interesting decisions, and it ends what feels like one or two rounds too soon—but it has its rounds-countdown running the entire time, so at least you know it’s coming. Honestly, I suspect that adding more turns would only make it feel like it had a runaway winner problem; I suspect it’s been tested to show that the outcome is achievable in exactly this number of rounds and not very alterable when given more. I like the stories, I love the artwork, and I look forward to sharing it with new people this year. If I can come up with the money, I’d love to add City of Iron & Islebound next to it on the shelf, though I am a bit miffed about how they handle Kickstarter stretch goals.

EDISON: I’m guessing they don’t include them in the retail version, based on your tone.

TEEL: Exactly. Either you backed the Kickstarter and get the full game experience with the best components, or you buy it at retail and get a little less. I’d prefer to be able to buy directly from the publisher and get the extras, or buy the extras in a separate pack for more money—not being able ever to get the full game is almost reason enough never to buy the game at all.

EDISON: That seems a bit extreme, don’t you think? What sorts of extras did you get for Above and Below for backing it on Kickstarter?

TEEL: They recently emailed me a PDF containing two more sets of stories for your explorations to take you on—literally hundreds of new stories that won’t be available to anyone else. Plus extra components to reach those stories, plus several unique villagers, plus some extra components to add new game modes and increase replayability. They amount to one extra punch board and a PDF, and I have them and anyone who buys at retail does not. Can not. It baffles the mind.

EDISON: Well, perhaps you can get someone’s used Kickstarter editions of those other games, someday.

TEEL: Maybe. I much prefer TMG’s policies with regard to Kickstarter stretch goals: They make the game better for everyone who buys the game. For example in Scoville, game number six on the list–

EDISON: Whoa, there! You don’t think you’re being a little too organized now, do you?

TEEL: We’ve been writing this off and on for almost 24 hours and have spent at least 8 hours writing, but there are four more games remaining to write about. Are you encouraging me to proceed at random and go on more long tangents?

EDISON: No.

TEEL: Because I can.

EDISON: No. Please.

TEEL: And I was planning to. The final game on my list, number eleven, is another TMG game, so I was going to talk about it after Scoville.

EDISON: Number eleven? Your top ten list has eleven games on it? Doesn’t that mean the game doesn’t make the cut?

TEEL: It definitely does make the cut, and all told we’ll have talked about at least thirteen games, so stop worrying about the numbers and look at this game board:

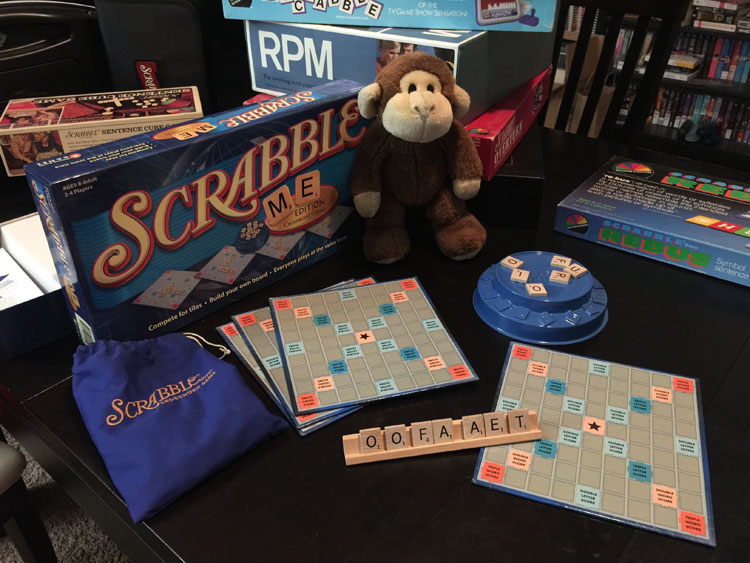

TEEL: Look close. The board has cut-outs for these awesome custom pepper-shaped bits. There are little custom farmer-shaped meeples that walk around on the board breeding peppers during the game. The peppers come in nine colors, four heights, and one of them is glittery/clear acrylic!

TEEL: All those things were Kickstarter stretch goals and some were backer suggestions. Originally, they were going to use colored cubes (and other boxes of the varying heights and colors) for the peppers, because they didn’t think it would be stable and were worried the non-standard orientation of the peppers would make reading the status of the board at a glance a potential gameplay challenge. Backers made suggestions, there was much conversation, and TMG communicated with their manufacturers about costs and options—and they came back with new and improved stretch goals for pepper-shaped bits and a board with recessed pepper-shaped cutouts for the bits to fit into so the board would remain readable and the peppers would remain stable. We hit all those goals (and the ones they’d originally planned, for the farmer, and more recipes) and we came together as a community to suggest recipe names for the different hot sauces you can make from the peppers you farm in the game, and if you find a copy of Scoville on the shelf at your FLGS, it’s all in the box. It’s all there. All the upgrades. If you didn’t hear about Scoville during the one month it was on Kickstarter in mid-2014, you don’t miss out on bits for a sixth player, or custom-shaped bits, or an upgraded board, or more recipe cards. You get it all.

EDISON: That sounds like a sound business decision. Fewer SKUs, easier distribution & manufacturing, and customers who find your products late aren’t put in a position of feeling like they’re missing out on the complete experience. How does it play?

TEEL: Very different from almost every game I’ve ever played. You plant peppers into the field, and depending on what colors are adjacent, you can pick peppers of other colors. You walk your little farmer around the board, but his movements are very restricted and become more restricted by other players’ farmers, which you can’t move through, so you’ve got to try to plan your movements while taking into account what other players may be after and then there’s the matter of turn order: I’m not thrilled with auction mechanics, especially for turn order, but if you absolutely need to move first (or last, if you want someone out of your way), you’re obliged to try to bid more than them in the auction to secure your preferred place in the turn order. As I alluded to, there are recipes to try to complete, which require complex sets of specific colors of peppers, and easier-to-achieve “market orders” which usually only need you to provide one or two peppers for a much smaller bonus.

EDISON: Sounds like a lot of moving parts. How easy is it to teach?

TEEL: It’s one of those moderately-easy-to-learn, challenging to master games. Most groups I’ve played with have only felt they were beginning to get a handle on what they’d done wrong in the first half of the game as the end of the second half began to close in on them—at least in their first game. But, at least for myself, that hasn’t diminished from the fun of just running around in a field, planting and picking peppers, and making hot sauces. Sometimes I can win, sometimes I end up having fun trying and failing to get the pepper combinations I’m looking for while running haphazardly around the field. I particularly like that it supports up to six players but plays reasonably well with two. The field certainly feels more claustrophobic and remains cramped for longer at two players, since it takes more turns to get the same number of peppers planted, but by the end of the game there’s plenty going on but not so much that players aren’t still stepping on one another’s toes; it’s a nice balance.

EDISON: The theme is certainly unique. It and Patchwork are possibly the most unexpectedly-themed games on the list. Possibly in your collection as a whole.

TEEL: Well, the next game I wanted to talk about is Aquasphere, my number eleven. It’s set in a futuristic undersea research facility—a set of underwater domes on the floor of the ocean where scientists, engineers, and their army of tiny programmable robots do science.

EDISON: Clearly, an everyday theme for board games.

TEEL: It’s not zombies!

EDISON: No, but it made your list despite dropping below the traditional cutoff point for a top-ten list. Why was that?

TEEL: It’s another one where the theme and mechanics are really well-integrated. You can play to win, but if you don’t want to take too long figuring out every action or planning multiple rounds ahead, you can also just run around in an undersea lab, playing with your robots, tangling with “Octopods” (little tentacled creatures which keep sneaking into the lab), deploying submarines, and otherwise having a blast in what amounts to the world of Sealab 2021 or The Abyss. Your scientist & robot meeples have no backgrounds, names, or personality, but the entire scenario is rife with flavor and you can really put yourself into their shoes. Mechanically: It’s a Stefan Feld. If you’ve played a Stefan Feld game, such as the wonderful Castles of Burgundy or the ever-popular Trajan, you have some idea what it might be like to play Aquasphere—it’s a Feld set in an undersea research base. Some people love a Feld (they’re even designed to be collectible), some people don’t. I quite enjoy them.

EDISON: And you said you got this one on Kickstarter? What sorts of stretch goals did it have?

TEEL: None. TMG is not the original publisher of Aquasphere, but they obtained the North American (and perhaps Australian?) distribution rights, and worked with the original publisher on the English-language translation. The Kickstarter was very short, there were no stretch goals, it was literally only to gauge interest so they wouldn’t over-manufacture. I didn’t have the money that week, so I wasn’t actually a backer. Of course, it seems they may have tapped most of the market during the Kickstarter, because very quickly after delivery to backers, TMG began putting it on sales. I got it for the discounted Kickstarter price, and was playing it within a couple weeks of backers—because at that point I did have the money. Just this week I saw it on sale for half of what I paid; if you can get Aquasphere for $40 or less, it’s certainly worth it, in my opinion. For $20, don’t hesitate. It’s a great little puzzle with a unique SciFi theme.

EDISON: Which brings us to number nine and number ten, by process of elimination. Which will you leave for last? My money is on nine.

TEEL: That’s a smart bet, largely because number ten is easier to talk about. It’s Entropy. I fell in love with the art for the game at first glance. It’s beautiful. I particularly love the way the different sets of cards come together to form coherent panoramas of the five alien worlds. When I was first glancing over the Kickstarter the other thing which I liked about it was that they were working with an author to write a novella telling the backstory of the worlds/characters with which Entropy takes place, and had produced a soundtrack for the game, as well. It wasn’t merely a small card game with great art, it was part of a coherent multimedia experience, and it wasn’t the first game they’d gone to those lengths for. I ended up pledging not only for Entropy, but also to get their prior Kickstarted game, Rise to Power, and all the multimedia goodies for both games.

EDISON: Were the stories any good? Do you refer to them when you play? Do they give the game the depth you were wishing were in Above and Below?

TEEL: *ahem* Err… I haven’t actually sat down and read the novellas, yet. Or listened to the soundtrack. In fact, I hadn’t even bothered to learn about the gameplay of either game when I pledged. I simply wanted to support that sort of game development. Because that’s just the sort of thing I can see myself wanting to do and backing down from, imagining there’s no market.

EDISON: Okay, but Entropy made it to your best-games list, so it must be fun, right? Even without the backstories.

TEEL: It is. It plays fast, supports up to six players, it’s super-easy to teach, and it’s pretty satisfying when you can figure out your opponents and get your reality to come together in front of you. The core concept is that your reality (and the realities of your opponents) has shattered into pieces which are all jumbled up in the “Nexus” (e.g.: a deck of cards) and the winner is the first one to piece their reality back together—by any means possible, including substituting “wild” fragments of reality for their own (but never fragments of their opponents’ realities). The game is played via simultaneous action selection: Each player has five cards which are identical to one another’s and one card (or two, with the Ronin) which has a unique action for their character. Each player selects the one action they want to attempt for that turn, simultaneously and in secret, and then everyone reveals their selections at once. Any players who selected the same action (all the unique cards are numbered the same, so they clash too) “clash” and they don’t get to take their action (unless they have the “Anchor”—which immediately returns to the Nexus when its possessor clashes). Everyone else resolves their actions in ascending numerical order.

TEEL: The actions let you do things like take fragments from the Nexus, steal certain fragments from other players, “reveal” your face-down fragments (locking them in, if they’re yours, so they can’t be stolen), taking the Anchor, et cetera. Entropy plays almost as quickly with 5 players (the most I’ve tried, so far) as it does with two, though there are a lot more clashes with more players. Luckily, if you’re involved in three or more clashes in a round (of four actions, before you take all your used action cards back into your hand and the Nexus re-shuffles), you have a chance to get a free fragment of your reality, so there’s some consolation if you’re particularly bad at reading your opponents. (Or if they’re particularly good at reading you.) Entropy is fun, it’s fast-paced, it’s beautiful, and it’s satisfying to work toward rebuilding your reality. Trying to figure out which actions to take and in what order is a great little puzzle which is a little different with every group, every shuffle, every round.

EDISON: What about their other game, Rise to Power? Why isn’t it on the list?

TEEL: It’s good, but it’s not great. It’s possible I simply haven’t played it enough times to really appreciate it, or that all the different in-box expansions add a lot to the gameplay which is missing from the base game—but the one relates to the other; I don’t want to try adding complications to the game when playing with anyone who has never played it before, but I’ve never yet been able to play it exclusively with people who already knew how to play the base game. So I don’t even know all the expansion rules, myself, at this point. I think it’s great they hit all those stretch goals (in a campaign I never saw) and added all that content & extras. I especially appreciate that it’s all in the retail version of the game. But the base game is just complex enough that it’s too much for our pie shop game night group, and too much to introduce to other new people with any more complexities. It’s a good game, but I’m not sure whether it’s a great game. Entropy is a great game.

EDISON: That seems reasonable. Any idea what they’re working on next?

TEEL: They recently did another Kickstarter—this time for a card game about building hamburgers. The artwork didn’t get me, there’s no backstory or soundtrack, the theme does very little to entice me, and the gameplay looked … uninspiring? I might have pledged (even with the expensive shipping from Australia) if so much of my board gaming budget hadn’t already been spoken for at the time, just to support the company—but my budget was already spoken for.

EDISON: That’s too bad. Hopefully you’ll be more engaged by their next game. But before you begin daydreaming about that, I believe it’s time to move on to the last game on your list, number nine of eleven. We’re nearly finished!

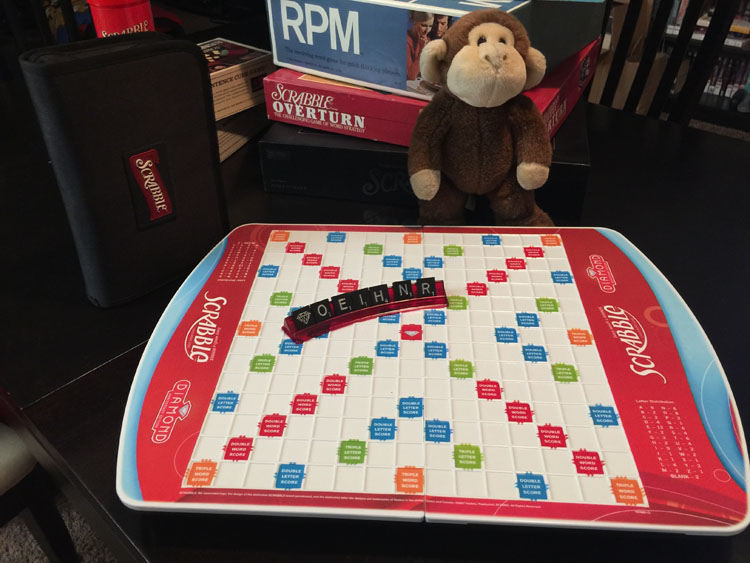

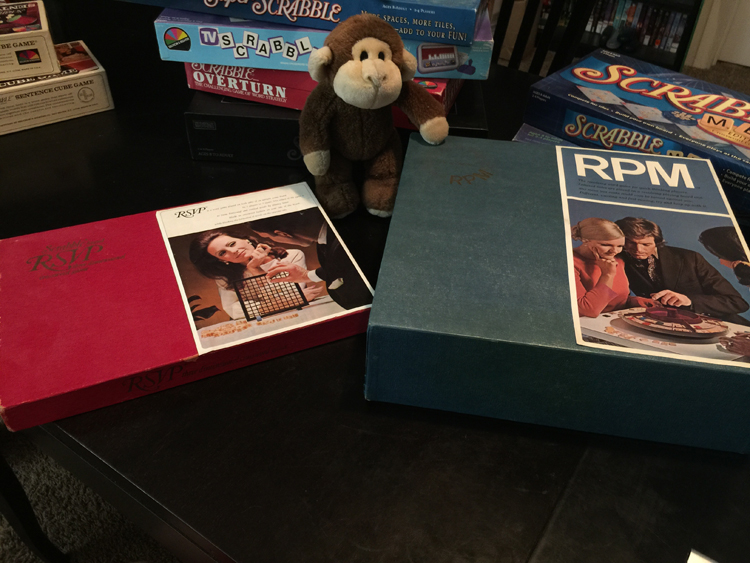

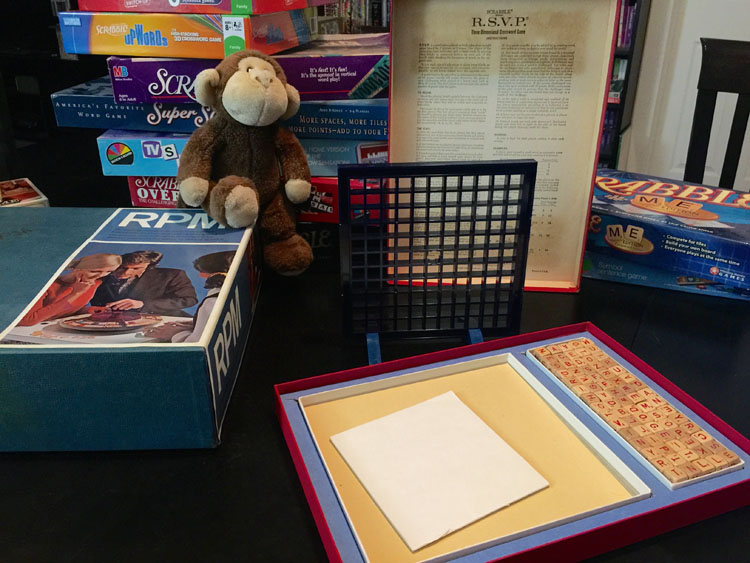

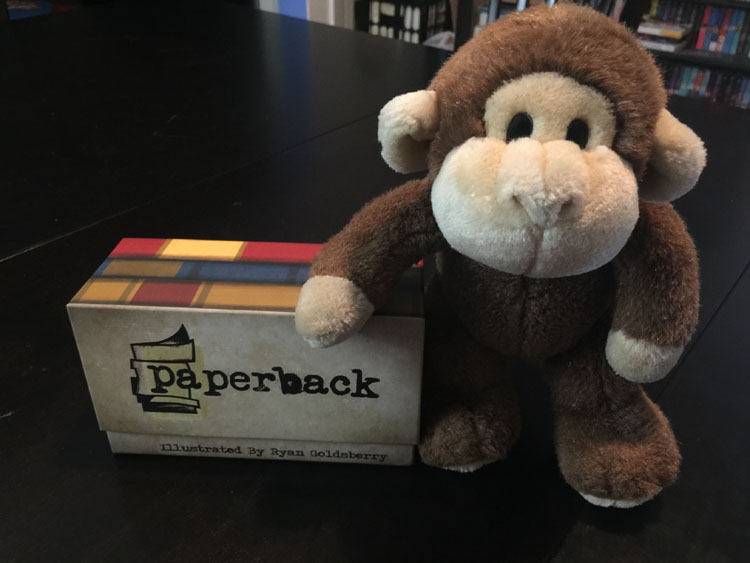

TEEL: Correct. Almost done. This game may end up moving up my actual rankings when I’ve played it more, but I didn’t receive the board for it until about a month ago. It’s by the designer of my all-time number two game (right behind Scrabble), Paperback, Tim Fowers, and features neat artwork by the same artist who worked on Paperback, Ryan Goldsberry.

EDISON: Is it another word-building or literary game?

TEEL: Not even a little bit. It’s a cooperative heist game called Burgle Bros.. Players play as a team of experienced burglars breaking into a highly-secure facility to crack the safes, steal the loot, and get to the roof without anyone getting caught. Each different burglar has unique abilities, each room of the building has different effects, and there are guards patrolling the building—all aspects of which are randomized each play-through, so it’s a different experience every time. The rooms have everything from alarmed sensors of every type (motion sensors, laser grids, fingerprint scanners, et cetera) to basic roadblocks (deadbolts, keypads) and common rooms (atriums where you can be seen from above/below, lavatories which give you extra hiding places, et cetera) as well as stairwells connecting different floors. The default-difficulty scenario has three floors, and if you have only the game you lay the floors out side by side like blueprints—but I love Paperback so much and had so much faith in the idea of Burgle Bros. that I put down the extra money and ordered the optional High Rise tower:

EDISON: That’s pretty impressive. It doesn’t come close to fitting in the box, of course, but it’s very impressive. How does it play? Do you have enough room to reach everything & see all the rooms easily?

TEEL: Oh, yeah. Plenty of height between floors without being too tall for short people to see what’s happening on the third floor—though everyone has to stand once the action moves to the third floor. Some people seem to have trouble with the spatial dynamics of the side-by-side-on-a-table version of the floors layout, but which floor is directly above/below a space is entirely obvious with the High Rise tower/board. The only complaint I have with the High Rise is that it isn’t always easy to put together or take apart, but it also sometimes tries to come [partially] apart during play; the design could perhaps have used a little more polish before shipping to backers.

EDISON: Have you actually had a problem with it coming apart during play? Like, did it fall down or shift or anything?

TEEL: Nothing like that. But sometimes one of the legs will come loose on a level or two, slipping out of joint by a quarter inch or so, threatening to come free. If we didn’t notice it getting wobbly, it might have led to real instability, but it’s pretty obvious when it’s slipping, and you can push it back together in a second or two. I heard Tim was working on an improved version, and when I hear more I’ll probably order it as soon as my budget allows.

EDISON: That doesn’t sound so bad. And you enjoy the gameplay?

TEEL: So far. As I said, I’ve only had it a few weeks and have been focused on other games at home (Ugh, Pandemic Legacy), but from what I’ve seen, it’s a hoot. It’s also the sort of cooperative game where one player’s bad decisions can sabotage the entire team (since if any one player gets caught, we all lose) and where one or two players could end up “quarterbacking” the entire game, making decisions for everyone the entire time. I’ve already found one person I’ll never play it with again (total sabotage), and I do my best not to quarterback, myself. It also has great potential as a solo or solo-multiplayer game, so you can expect to play it with me soon, Ed, and see for yourself how you like it.

EDISON: That sounds nice. Can I expect to do another piece like this, any time soon?

TEEL: Perhaps. This best-of-the-year list has been on my mind for several weeks, but I don’t have anything else specific in mind so it might be a bit. One thing I’ve been considering is doing in-depth discussions on individual games, or sets of games in the case of things like Agricola & Caverna, or Dungeon Lords and Dungeon Petz.

EDISON: I’m definitely up for more projects, especially if you actually let me play the games before we begin. I hardly had anything to add to this one, because I’ve never played any of the games on the list.

TEEL: Except 504.

EDISON: Which wasn’t actually on the list.

TEEL: Right. Well, maybe after another five games we’ll write a long piece about 504, then, to start.

EDISON: Or perhaps some of these other new-in-2015 games you bought but haven’t played enough to make it on the list yet, like Orléans, Portal, and The Bloody Inn?

TEEL: Perhaps.

TEEL: I’m not by myself, Edison. I have you. And the cats. And all these games.

TEEL: I’m not by myself, Edison. I have you. And the cats. And all these games.