This content is available to you for free thanks to the support of my Patreon’s generous supporters. If you enjoy it, please consider pledging to support future work.

EDISON: Is this it? Looks like we may finally get a short “review”, this time.

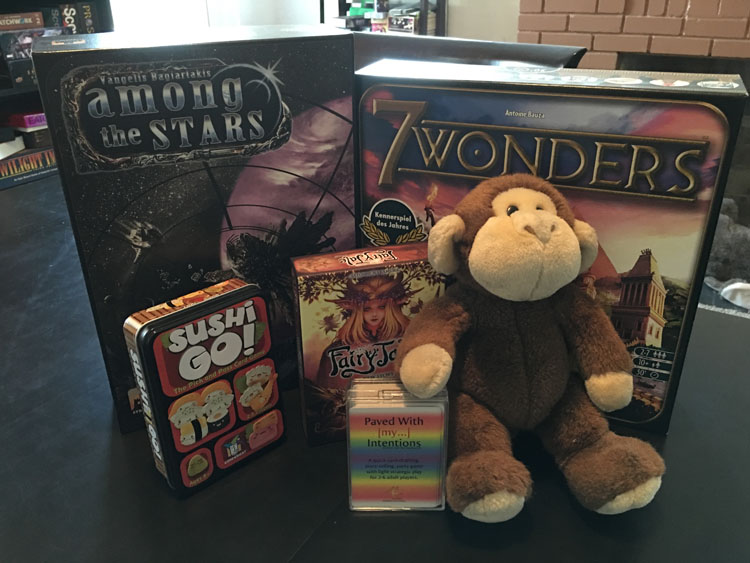

TEEL: Seems to be; I went over every game in my collection, and these are the only ones which use drafting as a central game mechanism.

EDISON: …are we going to head off on a long tangent about all the games which use drafting as a non-central mechanism, then?

TEEL: I guess so, since you asked so nicely.

EDISON: That’s not what I…

TEEL: Too late!

EDISON: *sigh*

TEEL: I’ll try to be brief.

EDISON: Like that ever works…

TEEL: There are plenty of other games that feature drafting, in one form or another, and which use it to greater or lesser extent, but I only have a couple of others in my own collection, and have only played one or two others beyond that, so it shouldn’t be too long a tangent. Mostly, games seem to use a small amount of drafting during setup or, more properly, in a sort of prologue mini-game—games like Seasons, Mage Tower, and Agricola (in a variant I’ve never actually attempted) let players draft a small number of cards which represent a small aspect of future gameplay.

TEEL: Unfortunately, this sort of design is nearly antithetical to my general philosophies and preferences regarding board games: They favor expertise, and handicap new and novice players. The cards you draft at the beginning of the game, while a small part of the game mechanically, tend to act as levers to spell the difference between having a very strong game and a very weak one—but the only way to know which cards to select in the draft is to already be quite experienced with the game.

EDISON: So the first time you play, you can only guess which cards will actually work together to help you, whereas expert players can strategically manipulate the draft to ensure they get an unbeatable starting position. For a certain type of gamer, I’m sure that sounds like a really good thing—if a group were playing a game over and over again so that everyone were at least moderately experienced with the game, then the draft makes sense and can allow players to craft a strategy from whatever random cards get drawn, rather than pursuing the same formula for success in every play-through. The draft adds variety, for a group that repeats the same game many times.

TEEL: Which sounds fine, but as we’ve discussed before, I prefer to get my variety by playing a large number of games—and loathe expertise.

EDISON: Which is still a little ridiculous.

TEEL: I’ve been giving my position a little thought since the last time we sat down together, and I think I have some clarifications: I’m not wholly against expertise of all kinds. Certainly, I’m glad there are expert plumbers and expert surgeons and expert mathematicians and expert chefs and many other sorts of experts in the world. I’m even an expert in several areas, myself, and strive from time to time to reach expertise in several additional areas. Expertise, itself, is not the problem.

EDISON: So what is the problem?

TEEL: Games are play. They’re a leisure activity. I totally respect someone who puts in the effort to become an expert in their field, or in a creative or productive endeavor, or even in something relatively abstract like meditation or theology. On the other hand, I have mostly disdain for people who put in so much effort to become an expert at a recreational activity. Professional sports players represent some of the worst of this and, to me; professional sports as a whole represent a massive waste of time, money, effort, and cultural potential. Play can serve a lot of purposes, but this sort of twisted manipulation of recreational activities into narrow, competitive, extremely serious pursuits, and especially into businesses designed not to create more play but to extract the most money possible from the least amount of play—these are horrible, evil things to be scorned.

EDISON: That’s quite a strong opinion, but it seems generally in line with your apparent anti-competitive preferences within games—at least, conceptually. When you’re actually playing games, it certainly seems like you’re striving to compete and win, much of the time.

TEEL: I’ll try to pay more attention to it, but as far as I’m consciously aware, I’m only trying to strive to do my best and to have the most fun. More like a runner trying to get their best time than like a runner in a race trying to beat the other runners. I know I certainly try to help other players, my “competition”, make the best plays possible, pointing out alternate strategies and tactics which may help them do their best as well.

EDISON: Which is weird, by the way. Everything about how you play games is a little weird, Teel, and I don’t mean that you sometimes play them with a stuffed monkey instead of other human beings.

TEEL: I know, I know, but deviating from majorities and standards isn’t, in and of itself, a bad thing. Most of my best work has come out of my own weirdnesses.

EDISON: We can all see where that’s gotten you, though. You write weird books, draw weird comics, design weird games, present a weird brand to the world, and then you sell very, very few books, comics, games, et cetera. Have you considered trying to be less weird?

TEEL: Ugh, yes. You missed most of that, while you were galavanting around the globe with your own weird friends, but I tried writing formulaic pop fiction for a few years, I tried painting what people were asking to buy at the art walks, and although I didn’t do much to alter my weird vision for the game, I tried marketing Teratozoic in a very normal, traditional, and relatively mainstream way. Each time I tried this, it resulted in a nervous breakdown followed by a cessation of creation (and further separation from the world)—I’ve painted roughly five paintings in the five years since trying to be commercial at art walks & festivals broke my spirit, I haven’t written anything substantial until this review series since trying to write & sell formulaic pop fiction broke my brain about three years ago, and haven’t been able to work on any games beyond semi-functional prototypes since Teratozoic shipped; the dark cloud of marketing and sales, manufacturing complexities and scale, and the expected year-long grinding down of my soul by the toothy gears of “market realities” between a finished design and shipping the last copy—it all makes it too hard to let myself reach a finished design, any more.

EDISON: You keep going really dark and personal in these things. Aren’t they meant to be board game reviews? We’ve barely mentioned board games, but you’re digging deep into your own depression and anxiety.

TEEL: You asked whether I’d considered trying to be less weird. I was explaining that I have, and that it kills me. Grinds me down. Snuffs out my creativity. Leaves me a paranoid shut-in. I was much better off being weird and being okay with being weird. I’m trying to be okay with it again, and somehow learning to be okay with the fact that nothing I do is worth anything according to “the market”, regardless of how normal I try to make it or how weird I let it be—if I could more thoroughly accept that there’s no money in being me, and a terrible combination of no money and terrible emotional and psychological suffering in trying to be normal, I suspect I’ll have a much brighter future.

EDISON: Which, I suppose, is why you’re here talking to me about board games, right now. This is you being yourself, creating what you enjoy creating, and sharing it out to the world without any concern for its marketability or a return on your investment.

TEEL: Something like that. Plus, I have a lot of thoughts about games and things, and blogging is dead.

EDISON: So should we get back to it? Would you like to play a game, first, or get into a long narrative about how and why you acquired these games?

TEEL: Uhh… I guess we could run through 7 Wonders. I’ve never tried the 2-player variant, and it’s technically the first drafting game I ever played.

EDISON: There’s a much bigger difference between playing a board game with a stuffed monkey and playing a board game which requires a dummy player than I would have expected.

TEEL: Certainly when the game expects players to use the dummy player strategically, as 7 Wonders does, yes. There’s a huge difference between one, which amounts to role-playing or simulating multiple personalities, and the other, which strongly favors highly competitive take-that style choices—frequently in trying to decide what cards to have the “free city” play, the main consideration had to be “what cards do I want to keep Edison from getting?”.

EDISON: Whereas when I’m playing my own turns I’m primarily concerned with what’s going to improve my position, sure. The free city ended up about a third behind our nearly-tied scores, because neither of us was in any way making choices to try to create the best free city; we were using the free city as a way to further manipulate which cards and resources the other would have access to.

TEEL: Congratulations on your win, by the way. You did well, despite it being your first game—which is exactly what I keep talking about; I prefer games which are accessible to new players!

EDISON: I only won by one point, and if I’d remembered I could discard for coins sooner, I might have done a bit better. There are certainly advantages to a little experience. Being able to plan out which cards would be coming back to me and being able to see what resources you had available so I could know for certain that you couldn’t afford a particular card yet made for a lot to try to hold in my head at once. The extra card drawn to the player in charge of the free city each hand was a real monkey wrench, though; I think I’d prefer to play it with three or more players, so the game state would be knowable after two turns.

TEEL: Well, this is where the expertise problem rears its ugly head: The game state is mostly knowable, because the cards dealt out in a three player game (which are the same set used in the two player game) are the same every single time. You could memorize them. The same is true for every other player count—a specific subset of the cards is used, to try to maintain balance.

EDISON: Which explains the long, tedious setup procedure. I suppose it gets easier the more players you have?

TEEL: It stays about the same unless you’re playing with the full seven-player limit; you still need to sift through every single card in each of three sets, regardless of which subsets you’re pulling out. This means that setup is best/easiest with seven players. Play is a different matter: With a full set of seven players, you never see any of your passed cards again.

EDISON: So how can you plan ahead? And why would you pay attention to your neighbors at all? I mean, except for the military strength of the two closest players… but as I learned in the last couple of hands, people can surprise you—it has to be even worse when the cards are effectively random when they reach you, rather than a known set you can plan around.

TEEL: I suspect the best players can, by observing what other people are playing, make an educated guess about what will and won’t come their way over the course of the game. I probably wouldn’t want to play with those people, though the more people you play with the more like multiplayer solitaire it becomes, so it might not be too much of a problem until endgame scoring. Always a surprise there, almost never good.

EDISON: I’m not sure how I feel about that. I mean, most of the points I could see as they were played, sure, but it wasn’t obvious how they’d add up or how they’d compare with other players. I can especially see how it might be worse if either of us had decided to go for science; the scoring on that looked a bit mad.

TEEL: It’s certainly… not intuitive, at first. But you can still tell at a glance, “Oh, that person has a lot of green cards, they’re going to win with science.” And then you can try to stop them from getting green cards.

EDISON: Yeah, even in a multiplayer game I can imagine that most of the interaction between players is in trying to manipulate which cards people have access to. Blocking them by building your wonder or discarding cards, or by playing them if you happen to have similar needs. I’m pretty sure that in the real world that sort of competition is actually, legally termed “anti-competitive”.

TEEL: You almost sound like you’re on my side of the debate over competitive play in games.

EDISON: I wouldn’t go that far, but it doesn’t seem like preventing your friends from playing is a very fun core mechanic for a game to rely on.

TEEL: Wait until we get to worker-placement games. In most of those, the primary (sometimes only) form of interaction between players is in blocking them from taking a specific action or gaining a specific resource. Some people decry them as being quite far on the multiplayer solitaire end of the spectrum, but what interaction they have tends to be some of the most brutal remaining in modern board gaming. It’s the equivalent of the thoroughly-decried “lose a turn” of yore.

EDISON: I don’t know whether I’d call it brutal, at least from what I can see in 7 Wonders—there are plenty of other good cards and options to take, each hand, even if the best one you were hoping for gets taken.

TEEL: Depending on that game, that’s usually also true in worker placement games. Still, even if you’re trying to play for fun, or mentally only competing with yourself, a few “non-optimal” turns can suck all the fun out of the game and keep you leagues away from your own best play. Interestingly, it seems to feel like an equal betrayal when a player intentionally blocks you as when they do it by accident in pursuit of their own agenda; the heart doesn’t seem to know the difference.

EDISON: There’s a lot the heart doesn’t understand.

TEEL: Very true.

EDISON: I suppose I should try to weasel out of you what you actually think about 7 Wonders, now. Try to get an opinion or two about games into this games review.

TEEL: Meh, I guess we can try that.

EDISON: So, Teel, what do you think of 7 Wonders?

TEEL: There’s a sort of a funny story about that, actually.

EDISON: Wait, no. Really? *sigh*

TEEL: Really. So, 7 Wonders was the first game I played where card drafting was the core mechanism—but I wasn’t aware that was what I was doing, at the time. A friend simply brought 7 Wonders with them to a game night one time, and we played it.

EDISON: Is that it? That’s the whole story?

TEEL: Almost. I played it, it was okay, and for at least a year afterward, I didn’t think of it again. I didn’t play it, I didn’t want to own it, I never asked for it to be brought again. Poof, gone. I own it now (which I’ll explain in a moment) and I suspect the only time it would ever approach the table is if we had six or seven people looking to play one game and at least a couple of them specifically requested 7 Wonders. I haven’t bought any expansions for it—though I’d consider them, if the price was right and my budget wasn’t already spent, if just to try the mechanics.

EDISON: You seemed to have an okay time playing it. What’s the deal?

TEEL: Meh. It’s okay. Not terrible, not amazing, and even though I apparently only own five card drafting games, 7 Wonders probably ranks third or fourth among them. …Actually, maybe fourth or fifth. Like the rest of these games, I bought it for research, because I wanted to study a variety of highly-rated card drafting games before spending a lot more time working on my own.

EDISON: We’ve discussed this before, though. You don’t mean Paved With [my…] Intentions. You designed and published that game before ordering any of these others. Before Teratozoic even reached Kickstarter.

TEEL: Correct. When I designed Paved With [my…] Intentions, I don’t think I even had a firm grasp on the idea of card drafting games. I certainly wasn’t aware I’d played one (7 Wonders) before, or that I was designing another. I’d been thinking a lot about interactive narratives, fiddling around with choose-your-own-style stories, and also thinking a lot about game design. They combined in my mind in a couple of ways, the first of which was this idea of presenting a very short story, one sentence or sentence-fragment at a time, via cards.

TEEL: Obviously, I’d seen drafting mechanisms before. I’d played 7 Wonders and Nightfall and Seasons and Mage Tower and more, and I already had the idea of “you get a hand of cards, you pick one and pass the rest, you repeat this with the new cards handed to you until there are no cards left” in my mind—I simply wasn’t thinking of it as card drafting until I had to sit down and think about how to describe the game I’d designed, and later to post it on BGG.

TEEL: Honestly, for me that’s the best way to create anything—totally free from constraints and labels and preconceptions, not knowing what you’re doing or where you’re going and not having a clear intention in mind except to create the best whatever-this-is you’re able to create. Like these things you and I are doing now, Edison: I have no real idea how to describe them, how to write marketing copy or what to tag them or how to categorize them on Amazon, let alone imagining who would want to read them or what they would get out of them. But in part because of that ignorance, writing them is bliss. Just as designing Paved With [my…] Intentions was.

EDISON: With a name like that, I can’t imagine you were thinking about marketing or SEO or even customer comprehension and memorability, there. What does it even mean?

TEEL: The title makes sense in the context of the game. As I said, you build a short story out of little snippets on cards. The story fragments are all color-coded and each player only gets one card of each color, then reads them in a specific order (white, purple, blue, green, yellow, orange, red—they correspond to the 7 chakras). By so tightly controlling the cards in this way, I was able to ensure that they all work together correctly— no matter which cards you select from the deck, as long as you read them in the correct order they form a coherent and valid [though frequently abstract or weird] story.

EDISON: It sounds interesting, but it doesn’t sound like much of a game.

TEEL: Well, there were two other things. You remember about the dick-stabbers we talked about before? In addition to my thinking about interactive fiction and game design, I’d wanted since first hearing the phrase to design a game where a player actually had to make a choice between making love to a beautiful woman for ten points and stabbing yourself in the dick for eleven points. Paved With [my…] Intentions is that game.

EDISON: Really? What kind of stories does this thing tell?

TEEL: Depends on the cards you choose, and how many points you want in the end, but a little over half of them are pretty horrific, and most of the rest come together pretty twisted, in context.

EDISON: Do I want to play it? Should I even ask?

TEEL: We can play, if you want, but you can probably get the idea by looking at the cards. In order to implement the choice while also creating a lot more story options for the game, I made the cards two-ended; you can rotate them 180º to get [in most cases] either a positive-sounding story fragment or a terrible-sounding story fragment—and then I gave them scores; positive numbers for the “good” stories and negative numbers for the “awful” stories. By saying the absolute value of your total story score determines the winner, players remain free to choose whether to put together an all-good or all-awful story (if they’re playing for points) or whether to focus on putting together the most entertaining story they can from the fragments provided. I also said that a zero ties all scores, and ties are decided by voting on the best story, to add a little more depth of strategy for people who wanted that sort of thing.

EDISON: Have you ever scored a zero?

TEEL: It’s incredibly difficult, if you’re playing with a lot of people, which is usually when this game gets played. The base game supported six players, and a little while later I added a little expansion (Have You Met [my…] Family?) to expand that to ten. All told, there are a total of six hundred and forty million coherent stories within that little deck of cards—it’s got quite a broad probability space. Most players will tend toward seeing only ten to twenty million of them, since they’ll be trying to optimize their scores rather than explore the entirety of the story space.

EDISON: That’s still a very impressive number. I suppose you count that as stories you’ve written when talking about yourself as an author now, don’t you?

TEEL: Sometimes. Usually in a pretty jokey manner. It’s hard to quantify this sort of thing, though. With the cards, especially, but even with other forms of interactive story. I wrote a sort of CYO-story for a contest once, and while it has one beginning and it’s [mostly] about one character’s journey, it’s composed of (if I recall correctly) twenty-five distinct story chunks (many with a fair number of conditional/alternate internal formations, certainly, depending on how you reached them) which together allowed for one hundred unique paths through the story-space. Most paths through were about the length of a short story and all of them together were shorter than most short novels. But back to quantification: How many stories did I write? There were at least half a dozen endings, most with multiple variations (depending on your journey), and the overwhelming majority of them resulted in “good” endings (if not happy endings). There were paths where the protagonist changes. There were paths where nothing changes. It was a rich and varied experience, if you went through it enough times, and with enough care. (Doing a bit of math wouldn’t hurt—better than punching coordinates into a time machine at random, anyway!) So was it one story, or six, or twenty-five, or a hundred?

EDISON: I honestly don’t know, but I’m eager to read it, now. Is it still available, or did you archive it to the depths of the internet?

TEEL: As far as I know, it’s still available in the Future Voices app on iOS. They certainly treat it as one story, there, which seems quite reasonable to me. But with the game, with Paved With [my…] Intentions, if you have the expansion included there are ten distinct story frameworks to choose from, and which one you choose has a huge impact on the narrative you’re able to piece together. This goes back to the titles; on the first card of each story, the white card, there are one or two introductory paragraphs with two words printed in red instead of black. (Things like “my boss’s” or “my father’s” or “my nightmare’s”.) On many of the remaining cards, the colored cards, there are places where in the midst of the story fragment, in red, will be “[my…]”—and at the end of the game when each player reads their story aloud (Did I not mention that part? It’s great!) they substitute the red words from their white card into all their other cards.

EDISON: So the story will be about whatever the white card says it is. A story about their boss, or their father.

TEEL: And all the stories are written in first-person perspective, which makes reading the awful versions of the stories (and the mixed ones) especially awkward … or really fun at the right kinds of parties. Because some of the cards are telling stories about a crazy serial killer, and others are describing a recurring nightmare, while others are about dealing with your pets, your children, or your parents. It all becomes very personal, but usually ends up with an interesting twist or two, so every story is unique, and made more unique by the person reading it and the group they’re reading it to. Which makes me want to lean more toward the six hundred and forty million stories direction, honestly, if I thought a lot of people were actually playing it.

TEEL: On the other hand, I have a feeling like a story is hardly a story if no one has ever read it—which may be why having so few book sales bothers me so much. So maybe the game only contains as many stories as the number of people who play it.

EDISON: But at up to ten players per game, it’s surely outnumbered the number of stories you’ve written and published by other means, already!

TEEL: Certainly. Yes. Dozens and dozens of stories, at least. Speaking of a dozen, sixteen months ago I ordered fifteen copies of the game to try to sell—and I have a dozen left.

EDISON: That means you’ve sold three copies! Way to go!

TEEL: Five, with online POD sales…

EDISON: That’s more games than I’ve sold! More than almost every human in the world. You created something, you put it out there into the world, and a few people said, “Yes, this, I want more of this in my life! Thank you, Teel, for creating it!”

TEEL: You may be giving them more credit and thoughtfulness than is due. It’s just a little game.

EDISON: Isn’t this what we started out talking about, Teel? You’ve got to learn to disconnect your creative process from the need to be validated by commercial success! You’ve created an amazing thing in this little deck of cards, containing multitudes of unique stories and a platform for people who have never put together a story in their lives to craft a custom fiction about themselves in a matter of minutes. Don’t sell yourself short, here.

TEEL: Well how about this: The real reason I bought these drafting games to study, the project I wanted to do with them, I couldn’t figure out how to do right—at least not without driving myself insane. I really liked the idea of crafting a unique story through gameplay, and I wanted to be able to have players putting together a coherent multi-act story with interesting characters, a meaningful and interesting plot, and a satisfying resolution—all via game mechanisms. Still mostly a drafting game, I thought, but deeper and wider than Paved With [my…] Intentions, and more satisfying for experienced & serious gamers to play. Ideally, I wanted to design a game where game players would be satisfied with the game they’d played, and the stories they’d crafted would represent usable outlines which writers could use to write the story they’d blocked out during play as a full-length novel or screenplay.

EDISON: That sounds extremely ambitious. Really interesting, if you could pull it off, but I can see why you haven’t solved it quite yet.

TEEL: Quite yet?

TEEL: *sigh*

TEEL: Alas, a core feature required to make the game functional is that players craft formulaic fiction. The writing, reading, and even often the thinking about which is quite like drinking poison, for me. The closest I could probably come is to trick myself into doing the entire project as a deep satire of formulaic pop fiction—but I’m still quite unsettled by how my past attempts at this have been embraced by readers as what they were trying to satirize.

EDISON: You have to leave your readers out of your creative process, Teel. Forget about your potential future audience. Don’t think about how your games and stories will be received. Simply create. Make the best games you can. Tell the best stories you can. Don’t give up.

TEEL: I haven’t entirely given up, but I’ve definitely scrapped most of my work on the thing a couple of times, now. My latest thoughts on the game include worker placement and area majority mechanics, but the core idea is still crafting unique, coherent, multi-act stories through engaging gameplay. I don’t know whether it’ll go anywhere, or if I’ll be able to escape the anxiety of trying to actually publish & market a game to get it beyond a prototype, but I’m still thinking about it.

EDISON: Good. Now what did you learn from these other games?

TEEL: Let’s see… Sushi Go, which gets significantly more play than any of these others, showed me how little is needed to create compelling gameplay. It offers much of the same depth and the same interesting choices as 7 Wonders, but it’s remarkably easy to teach (even to non-gamers), it’s easier to score (and to understand scoring), and it plays in less time. Plus it’s super-cute.

EDISON: How does it play with two? Does it also require a dummy player?

TEEL: It plays fine with two, and doesn’t require a dummy—though it’s definitely more fun with four or five players. Cards like the Maki Rolls and Puddings aren’t as interesting with two players, since they each only offer points to two players out of the group. Of course, one of the things I really enjoy about Sushi Go is how obvious the scoring is—the number of points a card is worth is printed right on it, and doesn’t differ depending on what your neighbors are doing, or on comparing the end-game value of a currency with the apparent value of a card to determine relative/net-value; if you played the card or completed the set, you get the points. Likewise, there are no costs or pre-requisites; if there’s a card in your hand you want to play, it doesn’t matter what you played earlier; play any card you want.

EDISON: Doesn’t that take away some of the strategic depth? In 7 Wonders we spent a lot of turns simply playing resources to use on future turns—and the resources we each failed to have on hand had a meaningful impact on our late-game capabilities.

TEEL: There is a difference between complexity and depth.

EDISON: Do you know what that difference is? Do you think this is an example of that? You’re being annoyingly vague and condescending.

TEEL: I didn’t mean to be condescending, and yes, I was trying to say that this seems like an example where the added complexity of the resource management of 7 Wonders, especially at higher player counts where certain resources may never even reach your side of the table, don’t really represent any added depth—only a stumbling block. Much of the balance of the extra cards added with increasing player count is in keeping resource availability and expenditure balanced across the number of players in the game; most of the time, everything will work out in a very balanced way where everyone has access to most or all of the resources in the game within a budget of currency available to them through the same trade network they’re spending into.

TEEL: Which is a fancy way of saying: Most of the time, the resources (and currency) are a waste of everyone’s time.

TEEL: When the resources do come into play, it’s by making a player’s decisions for them—if you don’t have access to three ore, even with your neighbor’s resources, a card costing three ore has been ruled out for you not because you chose to pass on it but because a bad shuffle didn’t get enough ore to your side of the table earlier in the game. In Sushi Go, all the cards are options in every hand—so you actually get more interesting decisions from the same number of cards.

EDISON: You aren’t saying that the decisions are more interesting, but that there are more decisions, right?

TEEL: Both, I think. The decisions are mostly-as-interesting as those in 7 Wonders, and there are more decisions to make, since every card is available. On the whole, more interesting decisions—ambiguity intended.

EDISON: I guess I’ll have to take your word for it, since you don’t seem to want to open the box and play it with me. What about this other one, Fairy Tale? Can we play that?

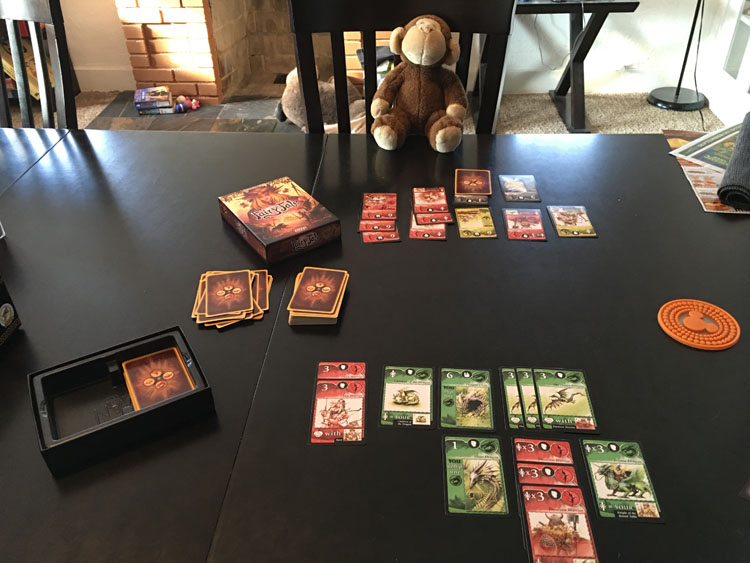

TEEL: I haven’t played that in a long while. I guess we could give it a run through.

EDISON: Well, that went fast.

TEEL: Yeah, I guess it’s a pretty quick game. Sorry I beat you by so much.

EDISON: I think I ought to have spent less time focused on trying to have any kind of long-term strategy and more time focused on blocking you from making huge combos. You had more points from half your cards than I got from my entire tableau.

TEEL: I was a little surprised you kept passing the cards I needed back to me.

EDISON: Toward the end I got a little distracted by trying to chain together a clever series of flipping and un-flipping actions to maximize my points, but when I finally had to decide which three cards to play I realized I didn’t have anything worthwhile in my hand.

TEEL: You netted twelve points from those three cards which, honestly, isn’t bad at all. Except for the big multipliers, which competitive play makes a challenge to assemble, the average card is worth less than four points—so that hand was above average.

EDISON: Possibly, but it’s the multipliers where winning and losing is decided. I think my main beef with Fairy Tale is that by the end of the game we’d only seen about forty percent of the deck. Combined with the very-short drafts, it turned out to be impossible and worthless to attempt any sort of long-term planning. There were plenty of cards which were designed to work with other cards, either a specific one or simply one from the same family—and while we knew within one pass of the cards whether their mate was immediately available, there were three or two or one more hands left to go where the needed cards might appear; doing a statistical analysis and making a rational decision based on the rarity information printed on each card isn’t exactly my idea of a fun time—or even something possible during a fast-paced card game intended to be played in under half an hour.

TEEL: Yep. You go through most of the deck with four players, so that’s less of an issue when you have a full game, but it’s clearly an issue. Additionally, even more of the strategy comes from take-that style actions, on account of the card-flipping mechanics.

EDISON: Most of them seemed only to affect my own cards.

TEEL: We were playing the “Basic” version of the game, which leaves out most of the PvP cards; I’ve never played the “Expert” version, and I don’t intend to. Though honestly, Fairy Tale has turned out to be a lot like Nightfall, Resident Evil, and Ascension; I haven’t played it since the month I bought it and studied it. The art is a little weird, the promise of a narrative (which was part of why I ordered it in the first place; I was led to believe the playing of the cards told stories) goes completely unfulfilled, and the mechanics strongly favor the sort of blocking-your-opponents play we were discussing earlier. Think about drafting five cards and discarding two of them, face-down; you can pretend it’s an innocent way to avoid playing a couple of less-than-great cards, but mathematically you’re best-off using it as a way to block your opponents from getting both the cards they need to get the most points and the cards they could use to hurt you.

EDISON: Are you sure you don’t want to try the Expert version with me? It’s an awfully quick game, and I’m not really another person…

TEEL: No, thanks. I don’t like that style of gameplay, even by myself. I also don’t expect to ever play the little expansion I paid extra for in Tiny Epic Galaxies—I paid the extra money to show my support for a local games publisher, not because I wanted to add an extra layer of PvP to the game.

EDISON: You really seem to take things to extremes. But I guess you know what you like.

TEEL: I’m trying to. Trying to avoid experiences I dislike, and to spend more time on experiences I do. For an example of an error I’m trying to avoid repeating, I probably played Tiny Epic Defenders at least twice as many times as I ought to have, considering how much I enjoy it.

EDISON: Which, from the sounds of it, isn’t very much?

TEEL: Correct. I kept playing it and playing it, giving it chance after chance, trying it with different groups, with the full version instead of the PnP, with different difficulty levels and different numbers of players—it never clicked. For me, it simply isn’t fun. I like the turn order mechanic, conceptually—though in practice it seems to make the game very unpredictable and swingy. I like supporting another local creator. I don’t like games designed and balanced with the idea that the players should lose most of the time. I don’t enjoy it in board games, and I really dislike it in video games—especially when they’ve designed the game around the idea of requiring expertise; I really, really, don’t want to have to work to enjoy my play. I don’t want to have to repeat the same mission/area/fight again and again until I’ve memorized it or mastered it in order to move on to the next (usually very similar in feel, if not in moment-to-moment execution, since you’ll have to master it, too)—this is not why I play games. Not at all.

TEEL: I want to win, or at least to feel like I succeeded. We discussed this after our game of Eminent Domain; I like to have the opportunity to bring my plans to fruition, usually to my satisfaction even when they don’t net me the most points in a game. I want to feel like I’m executing a strategy to the best of my ability. In board games, there’s also the social aspect of wanting to have a good time and to help my friends have a good time, too. I don’t like to go through a game with the nagging certainty that no matter what I do, I’m going to lose—or the general feeling that doing well in the game is largely out of my hands.

TEEL: This can be a narrow road to walk. Especially in cooperative games, you want the players to feel like they’re overcoming a challenge, not walking a cake-walk, while at the same time if you balance your game so they lose more often than they win (at least for me) it’s as bad as a cooperative game where, due to expertise, the game presents no challenge; either way we lose interest in ever opening the box again. I’m not 100% certain how to do it right.

EDISON: I suppose you know it when you see it?

TEEL: I dunno, sometimes?

EDISON: We’re closing in on the end of the list, here; is Among the Stars a shining example of hitting this balance, and you’ve left the best for last?

TEEL: If only I’d planned that far in advance. But no, I apparently have no idea what I’m doing, and have been largely addressing these games in random order. Among the Stars is pretty good. I really like the way the square cards get laid out to form your space station, and how their different adjacencies affect your score and ability to play future cards. I particularly appreciate the theme, at least out of this group; same as before, SciFi is appreciated, Fantasy is the opposite, historical games are hard to stomach and must have superior gameplay, and … Well, I guess I like sushi and cute art. But SciFi is my preferred genre, so Among the Stars gets a lot of points for being SciFi.

EDISON: How thematic is it? Can we play?

TEEL: I don’t really have time, right now. Mandy’s going to be coming home from work soon and I’ve got to make dinner. Among the Stars usually takes Mandy and I about forty minutes to play, and you and I always take a little longer at games with simultaneous actions, so … maybe another time? But here, look at the cards. The theme is pretty-well integrated into every card—at least in this base set. I don’t have any of the expansions at this point, and I’ve heard they make setup a little complicated and frustrating so I’ve been putting off on them. Anyway, you can see that the different classes of structures are color-coded, so administrative and security are blue and inter-species diplomacy and interaction is green and entertainment facilities are purple while military stuff is red.

EDISON: And then you get set bonuses for the colors? Or can only play next to the right colors?

TEEL: Lots of stuff like that, yes. It depends on the card. So, some cards require power and have to be placed within a couple spaces of a power plant. Gardens give you point bonuses if they aren’t placed near power plants or military stuff. Security offices score the most points if they’re entirely surrounded—giving your security staff then best access to facilities. Restaurants are worth more points if they’re near lots of different sorts of things—so they have a broad enough clientele to thrive. Transportation hubs are worth more points for every other transportation hub on your station. It goes on and on, and almost all adds to the cohesion of the theme and mechanics.

EDISON: How does it play two-player? Fairy Tale was frustrating in using a random-but-truncated deck. 7 Wonders curated a balanced deck for most player counts but required a dummy player for 2-players. What does Among the Stars do?

TEEL: A bit of both, I suppose. I think the original 2-player rules had dummy players, but the book includes (and the internet so strongly recommended to me) a variant adjustment that I’ve never played it any other way: For two players you use the same set of cards as the four-player version, both players draw an extra card at the beginning of each hand and then both players discard a card (in addition to the one they play or discard for coins) before passing. It’s a bit like the 7 Wonders dummy player, in that it gives you these out-of-left field extra cards all the time and an extra mechanism for blocking your opponent from getting a specific card, but there are so many extra cards (twice as many (relative to default hand size) as 7 Wonders, a full doubling of the number of cards passing through hands) and so many excellent ways to build a space station that we don’t get too much take-that feeling when we play. A lot of the time we find ourselves facing a hand of cards all of which we would love to have in our station, and having to choose which one of those wonderful cards we have to say goodbye to. Or two cards, if we run out of credits.

EDISON: What about the three-player game, then? Do you not go through the entire deck?

TEEL: This is part of what, apparently, makes having the expansions so frustrating to set up. In the base game there are effectively three different decks to begin with: The cards for three players, the cards to add with four players (or two), and a deck of “Special” facilities from which a set number of cards-per-player is added to ensure the deck draws out perfectly. This is much like the curated sub-decks of 7 Wonders, but lacking in player counts above four. The result is a quite well-balanced deck at any player count (2-4), and a deck which always looks like you’re drawing every card, which feels satisfying. In an effort to keep the game balanced when playing with the expansions, I hear there are rules and charts which go over in detail how many of which types of cards you should add and remove to maintain a well-balanced deck—it’s complicated and time-consuming enough that many players apparently set it up and then don’t change the mix, either for several games or until they buy the next expansion, even though it’s designed to be built fresh every play.

EDISON: Whereas with the base game, the variation from the Special cards being an incomplete set adds at least some variation from game to game.

TEEL: I’m starting to get to the bottom of that well, actually. It’ll probably only take a few more games before I won’t want to touch it again without an expansion—at least not for a long while. Partially it’s due to familiarity with all the cards in the game, but it’s also about expertise again. By being familiar with the entire set of cards and having built several space stations with them, I’m unintentionally developing a sort of mastery of the base game where I can tell at a glance which card I want and where to put it and even develop medium-term plans for the rest of the cards in the current draft based on knowing how everything works together. It’s terrible.

EDISON: Sounds lovely. Isn’t that what you were saying you wanted not long ago? Forming a plan, coming up with a strategy, and then being able to see it through? How is this different from that?

TEEL: Maybe it’s in the wondering. Wondering whether I’ll be able to see it through. Or maybe it’s in the novelty, too; wondering what cards I’ll see this time, and next round, and how they’ll work with the cards I’ve already seen. Novelty is very important, psychologically.

EDISON: And you’re clearly a slave to novelty; I’m sure it’s why your collection is so large, and why you’re satisfied playing a game only a few times and lose interest in a game after only a few plays.

TEEL: Speaking of which, I believe we’ve covered this part before, and I’ve got to go get started on supper. Do you mind if I–