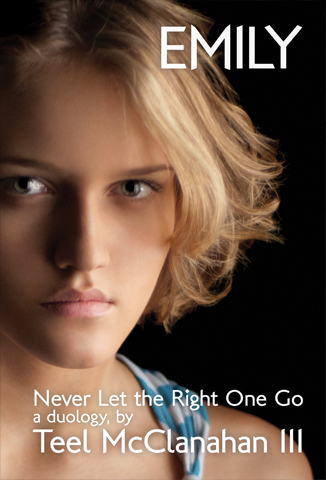

by Teel McClanahan III, Copyright © 2012

A Science Fiction novel; half of a two-book series

eBook

The eBook edition of Sophia (Never Let the Right One Go) is available under  .

.

Audiobook

The Audio version of Sophia was recorded in 2012, and was podcast on the Modern Evil Podcast and at Podiobooks.com in 27 parts, one per chapter. This MP3 Audiobook version contains the same basic recordings, but without intro/outro on every file.

You can get the eBook or audiobook for FREE, using these links:

SOLD OUT:

Hardback; 450pp, ISBN:978-1-934516-08-9; Limited edition of 50

About the book

At age 7, Sophia was struck down with a life-threatening disease. Faced with a choice between an unending life in the body of a child and her otherwise certain death, Sophia’s parents had her turned into a vampire.

Now, after 10 years of Christian home-schooling and near-total isolation, Sophia secretly plans on moving out the very night she turns 18. All her research, her online classes, and her natural curiosity have prepared Sophia mentally for the world she’s about to dive head-first into, but no amount of research could prepare her heart for falling in love with Joshua, the first young man she sees after donating her corneas the next day.

Her faith in God and her desire to heal the sick gives Sophia the strength to persevere through the pain of donation after donation, and her vampirism gives her the ability to grow her organs back again and again, but Sophia finds herself unequipped to face her suddenly-awakened lusts of the flesh and the ache in her heart for a deep, reciprocated love. After a shocking and painful first date with Joshua, it doesn’t take Sophia long to learn just how difficult the search for love can be, especially for a teenage vampire with a child’s body and a strong desire to avoid falling into sin.

(Click here to read the first 2 chapters of Sophia)

Books in this series:

About the Author

Teel is an independent author, artist, game designer & developer, creative visionary, podcaster, and publisher.

Teel is happily married to an English teacher and they live together in Phoenix, AZ with a grumpy old cat, a skittish young cat, and thousands of books, both read and to-be-read. Sophia and Emily (Never Let the Right One Go) are his seventeenth and eighteenth books, and there are plenty more trying to work their way into this world through the aperture of Teel’s imagination, hoping to be found and loved by readers like you.

Follow him on: Twitter, YouTube, and Goodreads

Which book should you read first?

Short answer: Read whichever you like first; I designed both Sophia and Emily to be introductory and primary.

Longer answer: Which book you read first will have a significant impact on how you see the world of Never Let the Right One Go, and how you see the characters, beliefs, and activities of whichever book you read second. Each book is designed to be a complete story, the story of one young woman as her eyes are opened to the world around her, and her life is changed as she steps out of her old comfort zones for the first time, but the paths taken and the end results are wildly different from one another. One of the books is told from the perspective of someone who sees the world as a dystopia, and is structured so as to demonstrate (as in a Euclidean proof) that the world is a dystopia, and the characters and plot are fashioned in the style of dystopian fiction both traditional and popular. The other book is told from the perspective of someone who sees the world as a utopia, and is structured so as to demonstrate that the world is utopian – or at least that everything which makes the world unique from our own has been an improvement both for the society and for the individual.

Based on the feedback of early readers who read both books I can also say that (probably) whichever book you read first you’ll like least, and whichever book you read last you’ll like most. After finishing one, they said they liked it, but after finishing both they preferred the other. Perhaps this is because people are convinced by whatever argument they’ve heard most recently, and each book is built as an argument for its own point of view; by reading the second argument, their perspective on the first is altered – usually reversed. Of course, there are other factors at play, as well. Maybe you can’t stand Nicholas, so reading Emily becomes difficult. Maybe you’re aggressively anti-religion, so Sophia’s Christian background and reliance on faith to get her through tough situations rubs you the wrong way. Maybe the long political and economic discourse in one is too dry, or the awkward and painful sexual situations in the other are outside your comfort zone. There are countless differences between the two books, any one of which may be the thing your opinion hinges upon.

None of these differences, however, puts one book ahead of the other. Both books cover roughly the same time period, the same few months of the same year. Both books introduce and explain the world in the course of the girls’ journeys, without repeating one another. The books are well-enough paralleled that going back and forth between them, one chapter at a time (as you would experience them by subscribing to the Modern Evil Podcast), is a reasonable and viable approach to Never Let the Right One Go, as a duology. (In fact, doing so will reveal even more about the differences and similarities between the girls and their lives – I recommend it for a re-read, rather than a first-read, as some of the story becomes even sweeter when you know what’s coming in both books.) Which book you read first is truly a matter of personal preference, or random chance, rather than any pre-determined order.

My personal preference: I prefer Sophia over Emily, personally. I think it’s the superior book, I think Sophia is the stronger character, and I think hers is the better story. I fundamentally disagree with the politics and basic beliefs of Emily, Nicholas, et al, and had a hard time writing them convincingly. I wrote Sophia (mostly) first, though a significant portion of the world-building I did only appears in Emily. I think starting with Sophia is the way to go, because I think it gives a better overall impression of the duology, though I also want to suggest that you start with Emily, since I want you to like Sophia better.

I know, I know, I’m no help. Sorry…

Read the first two chapters of Sophia:

Chapter 1

Tonight is the ten-year anniversary of my death, and next week is my eighteenth birthday. My parents wanted to celebrate today, instead of my birthday, because they think my resurrection is more monumental than my birth. What’s truly monumental is legally becoming an adult, so I convinced them to save the cake a few nights. I’m so excited to finally be allowed to see the world beyond the four walls of this house and those of the church across the street. I’ll be eighteen, and there won’t be anything my parents can do to stop me. Not any more. No more bedtime at 4AM, regardless of sunrise. No more home schooling; I’ve been doing college coursework online for years, and when the new semester starts next month I’ll finally be able to actually sit in a classroom like a normal person for the first time since Kindergarten! I’ll finally be able to interact with people my own age, face to face and in person!

Speaking of which, no more suffering through Sunday School with second graders for the 11th consecutive year! What a relief it’ll be to finally be able to study the Word of God at my own level for a change, or sing songs of worship with a little more complexity than ‘Jesus Loves Me’ and ‘Down In My Heart’. It’s like 1 Corinthians 13:11 says, “When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. But when I became an adult, I set aside childish ways.” I may still look like I’m seven years old, but my parents, my pastor, my teachers and all of you know I set aside my childish ways long ago. Or at least you should. And now that I’m finally, legally, going to be allowed to make my own decisions, I won’t have to put up with being treated like a child any more!

Sophia filled her friends-only online journal with her hopes and dreams, her frustrations and longing, her plans for her life once she was freed from the monotony it had become. It wasn’t that her life was particularly awful; Sophia had enough blood to drink, she had parents who loved her, a comfortable home in a good neighborhood, a church that welcomed her with open arms, and no reason to be anything but hopeful about her future; it was simply that Sophia was a teenage girl, and that was reason enough for anyone in the same situation to have something to complain about. Luckily for Sophia, her parents had made sure she was well-versed in the constantly evolving state of technology; she was much better at managing her online privacy controls than any flimsy lock on a cheap paper diary could have been, and her parents had rarely heard her voice a word of dissatisfaction.

Sophia’s parents were the sort of Christians for whom everything was wonderful, all the time, a blessing from God, no matter the situation. Sophia wasn’t entirely sure how they would react to reading her journal entries of the last few years, whether to pray in thanks to God that they’d been given yet another challenge to overcome and thereby strengthen their character, or to begin making intercessory prayer to turn Sophia’s heart from this internal darkness and to bolster her faith in God’s Will for her life; Sophia figured it would probably be both, with her Mom and her Dad taking turns thanking God for the situation and asking Him to change it. She thought it better to keep it a secret, at least for the next few nights.

“Sophia,” her mother called from upstairs, “are you ready to go? We don’t want to keep everyone waiting on your special night.”

Sophia finished her thought and hit ‘Post’, sending her words out to her small circle of trusted friends -none of whom she had yet met in person- and called back, “Yes, Mom, I’ll be right there!” She leapt across the room with startling alacrity and began getting ready, a literal blur of motion. After a decade of practice procrastinating, Sophia knew exactly what measure of her super-speed she could get away with while dressing before she began to tear her own clothes to shreds in the process. That her entire wardrobe consisted of conservatively-cut dresses, none shorter than mid-calf in length, certainly made it easier for her to get in and out of an outfit in record time. Brushing her hair took a few extra seconds because moving too rapidly would only make it more wild than it had been when she’d begun, but Sophia’s parents preferred such a simple style, she was stepping into her shoes and headed up the stairs before more than a handful of seconds had passed. “See?” Sophia asked, presenting herself for her mother’s inspection, “I’m ready.”

“Your father went ahead, as usual.”

“It doesn’t hurt to get a few extra prayers in,” Sophia replied.

They walked out the front door of their house into the cool nighttime air, and Sophia began to cross the soft grass of their front lawn while her mother locked up. She knew her father didn’t like anyone walking on his fastidiously maintained lawn, but Sophia figured she could get a little leeway on her resurrection day; her mother walked around the lawn, but didn’t say anything. Sophia especially liked the feeling of the cool, soft grass under her bare feet, but even just crossing the lawn in her shoes woke up a world of indescribably faint and beautiful scents and sensations to fill her lungs and cover her skin. Sophia prayed a little silent prayer of thanks to God for her supernatural senses as she relished in the beauty of this tiny, landscaped patch of His creation. She looked both ways down the empty residential street, then ignored the fact that it would have been safe to simply walk calmly across the road and leapt twenty-five feet in the air, landing softly on the precise place on the sidewalk she’d selected, with her hands pressed to her sides to keep her dress from billowing out and up and taking her modesty with it. She waited there for her mother to reach her side by conventional means, then took her mother’s hand and they walked into the chapel together.

Maribel and Agnes, two of the little old ladies in the congregation who never missed a service or a choice piece of gossip, were standing just inside the door whispering to one another when Sophia and her mother walked in. Their voices shifted from conspiratorial to congenial as they turned to face them, and Maribel said, “God bless you two on this glorious evening.”

Agnes said, “Happy resurrection day, Sophia. You’re so blessed to be among the first resurrection. Congratulations.”

Maribel continued, “I can’t believe it’s been ten whole years since you were in the hospital. What a hard time that was, for everyone. We should have known the Lord would replace our suffering with joy, just as he promised.”

“God has taught us all a little something about faith with little Sophia,” her mother replied, “and of the importance of persevering through what seem like inescapable problems and learning to rely on the Lord. It’s just like the story of Joseph; if he hadn’t been sold into slavery, beaten, accused, and thrown into prison for crimes he didn’t commit, he would never have had the strength of character to become ruler of the richest nation in the world, or the savior of the multitudes during the years of famine. We are all forged in the fires of the challenges we face, and strengthened by them for the challenges yet to come.”

Sophia had heard variations of this conversation repeated again and again over the years since she’d suffered and died, and while she knew it was true, and a good lesson if you’ve never heard it before, it was one she’d been hearing for what felt like her whole life. She’d begun to tune them out and look around to see who was already seated when Maribel addressed her directly, “At least you know what your challenges will be, Sophia. Back into the hospital, back into the pain and suffering,” she shook her head and took on a look of concern which may actually have been genuine, “I don’t think I’d be strong enough to take that on as a way of life, dear, but I’ll be praying for you. Do you know when your first surgery will be?”

“I can’t donate until I turn eighteen, next Tuesday. They always need bone marrow, and they usually need corneas, so I’ve been tentatively scheduled to donate both Wednesday night.”

“So soon?”

“If I could have been helping people sooner, I would have been. I know my blood is already saving lives in emergencies, which is good, and my corneas may restore someone’s vision, but my bone marrow could turn the course of a chronic disease around.” Sophia’s confidence in her words made her feel larger than her four foot frame, and she nearly forgot she was forced to literally look up to people like Maribel and Agnes. “They prefer to start us off with relatively minor donations, but hopefully within a couple more weeks I’ll be saving the lives of children with congenital defects or worse, children who, like me, may not have a lot of time to wait for replacement organs before they die. Wouldn’t you do anything you could to save a sick child’s life, Maribel? Being turned into a vampire may be an option for them, but it isn’t optimal; wouldn’t they be better off if they had the chance to grow up naturally?”

“Of course, of course, I…” Maribel stuttered. Sophia knew that Maribel, like most of the congregation over the age of about twenty, had opted out of organ donation when the new legislation had made opt-in the default for every citizen almost as long ago as she’d been dead. She knew their interpretation of the resurrection was like that of the Pharisees, that it was their literal, physical bodies which would be resurrected at the end of days, and that they wanted to keep those bodies whole for that reason. Considering the reality of the first resurrection, that of vampires, which was clearly a physical resurrection of a person’s dead body, Sophia could understand why they would cling to such a simplistic interpretation. It was the fact that vampires’ bodies are made whole upon resurrection, not to mention the omnipotence of God in general, which cast their aversion to having their own bodies used to save lives seem selfish and narrow-minded.

“I only wish I could donate my heart, too. Heart disease is still the number two killer among adults, and something like one in five hundred children have a bad heart, just waiting to fail. Only the unresurrected dead can donate their hearts,” concluded Sophia before leading her mother by the hand deeper into the church.

Her father saw them coming and waved, saying softly, “Sophia, would you mind helping us up here?” He knew Sophia’s hearing was good enough to hear him whisper from across the street, and didn’t bother to raise his voice.

“Dad wants me to help move the altar again,” Sophia told her mother, releasing her hand and skipping playfully toward the front of the church. “You know I’m not going to be able to move this thing while I’m recovering from surgery, right?” Sophia didn’t mention that she had no intention of remaining at home with them after she began her donations, or that she wanted to find a new church to attend, but she wanted her father and the pastor to be aware she wouldn’t always be around.

“We know,” said Pastor Rigby, clearing the last items from the altar’s surface so it could be moved safely, “and if you’ll help us again after tonight’s service, I think we’ve picked a good, semi-permanent spot for it.”

“Where do you want it for now?” The Pastor pointed, and Sophia wrapped her tiny arms around one end of the altar as though giving it a hug, squeezing the heavy stone between the palms of her hands. She lifted it as though it were light as a feather and moved it with delicate grace to the indicated place, gently setting nearly a ton of solid marble out of the way like so much folderol. Pastor Rigby and her father thanked Sophia and got to work replacing the array of displaced items to the top of the altar, and she joined her mother in the frontmost pew.

After a few minutes, the last of the congregation, including Sophia’s father, were seated and after giving a brief welcome, Pastor Rigby dove into the delivery of the night’s message. “As I’m sure you are all aware, tonight is not a night like every other for our community. Tonight is the anniversary of a great blessing which was bestowed upon us by the Lord, the First Resurrection of one of our own just ten short years ago.” There were already a few amens and a “Hallelujah!” rising from the congregation, and Sophia knew the Spirit of the Lord would be felt by everyone present, that night. “Young Sophia was not the first in the world, but she was the first from our little world, and she has been a brilliant light of Kingdom hope, shining upon us! She is an undeniable reminder among us that we are living in God’s own age, a time of great blessings and revelations, a time of miracles and of wonders.

“Our generation is witness to the true realization of the Great Commission, accompanied by the signs foretold in Mark 16. It was said that they would drive out demons, and lo, did they not remove the scourge of terror from the face of the Earth?” “Amen” “It was foretold that they will pick up snakes with their hands and whatever poison they drink will not harm them, and behold, are they not protected from dangers both animal and mineral, natural and man-made?” “Hallelujah,” and “Amen!” “We were told they would place their hands on the sick and they would be made well, and we have seen with our own eyes that they hold the power to heal in the palm of their hands! You, Michael, were you not struck down in the prime of your life by a drunk driver?” “Yes, father!” and from another, “Struck down!” “And were you not made whole again by the power of the blood?” Louder this time, “Yes, father!” and “Amen!” and “Hallelujah!” “The healing power of the blood has saved you, Michael!” “Amen!” “And little Sophia, poor, precious Sophia, was on her death bed just ten short years ago. She suffered, she weakened, and no worldly cure could be found for her. In the end, ten years ago to this day, our little Sophia died. Her organs simply could not sustain her. Science could not bring her back to us.” “Oh, no!” and “No sir!” “It was only by the grace of God and the power of His blood that Sophia was restored to life,” “Hallelujah!” “resurrected,” “Praise the Lord!” “and given new strength as a part of the Lord’s Great Commission, as we all are part!”

The congregation was in active dialog with Pastor Rigby by then, and actively praising and worshiping God with shouts and calls and raised hands as he continued, “Are we not in the most glorious age, the dawning of the Kingdom of God here on Earth? For millennia the church has struggled under the oppressive yoke of worldly governments. For centuries we have watched democracy itself fail to improve upon the tendency toward corruption and inequality which all man-made institutions are prey to, because of our weakness to the flesh. Finally, in our own time and before our own eyes we have seen the very hands and feet of Jesus Christ going to work to reform the world’s government. We have seen men of incorruptible flesh step up to the challenges of this corrupt world, and we have seen the good fruit of the power of the blood at work in the land. Lives saved, the sick healed, the poor and hungry clothed and fed, the mourning comforted, and the good examples created by those precious few like our little Sophia have finally set so many others on the straight path toward salvation and good works of their own! Our world was rapidly descending into Hell, but by the power of the blood, the same blood which brought our little Sophia back to us, we are now ascending on the wings of angels into Heaven!”

Pastor Rigby’s sermon went on like that for over an hour, the congregation burning hotter and hotter with the fire of the Holy Spirit, praising and worshiping God. Sophia, despite being self-conscious about being made the center of attention once again, was just as moved by the Spirit. By the end of the service, as she walked back across the street with her parents, she was almost convinced to continue attending the church after she moved out. Then her father said, “It’s too bad your resurrection day is in the summer. All the other kids your age are missing out when the Pastor gives a message like that this late at night,” and Sophia was reminded once again that her parents still thought of her as a seven-year-old girl most of the time. She bit her tongue and began putting together another post for her journal in her head.

Chapter 2

Sophia liked to read about vampires online. In part this was because she didn’t really know any other vampires. If she’d been turned just a few months later, new legislation would have applied to Sophia and she would have been expected, as an underage vampire, to attend one of the new vampire schools or at least to pass a sort of standardized test which was supposed to prove she was normalized enough to be able to get by in society. Instead, she was grandfathered in as an existing vampire and her parents successfully appealed to have Sophia exempted from both public schooling and standardized vampire testing; they also minimized her contact with the outside world, human and vampire alike. Other than what she saw in the news or read online, Sophia knew next-to-nothing about vampires, even though she was one. She’d been turned at such a young age, she couldn’t really remember much about being anything other than what she had been every moment since then; Sophia was like the proverbial fish who couldn’t really tell you much about water.

The other reason Sophia so liked to read about vampires was because it told her a lot about humans. Whether the journalists and bloggers and authors writing about vampires were human or vampire, they all seemed to write from a perspective of humanity being the baseline for all things; because of this, Sophia was able to begin to understand more of how she was different. She was able to see herself as abnormal, by looking through the eyes of other people. It was much more eye-opening than any comparison or conversation with her parents could be, since they were so gentle, loving, and deferent, trying always to make everything about Sophia’s life seem like it were normal and everyday. When she read about other vampires doing things like she did, and the way people wrote about it, Sophia could see that some of the things she took for granted were far from normal.

Some aspects of what set Sophia apart were easier for her to see. When Sophia accidentally cut herself while chopping vegetables for her parents’ supper, the wound had closed before she’d even noticed the blood and the only problem was washing the blood off the cutting board and the food; relative to the gamut of sensation she was subjected constantly to, the pain had hardly registered. The first time Sophia saw her mother accidentally cut herself while chopping vegetables, her mother shouted in pain and then bled and bled until the wound had been cleaned and dressed, and it would have taken more than a week to heal if she hadn’t gone in to get stitches – the doctor skipped the stitches and put a few drops of vampire blood on the wound, healing it completely in a moment. The next time her mother accidentally cut herself, once more she shouted in pain and bled and bled and then asked Sophia politely if she would mind sharing a drop or two of blood, to save them all some time and effort and pain – and from then on, Sophia’s parents never went to the doctor for minor injuries again.

Seeing the healing power of her blood first hand, working right before her eyes on herself or her parents, was one of the easiest differences from normal Sophia could see. Her mother’s blood was a sign of injury, but Sophia’s blood was the solution to injury. Her mother’s body could heal on its own, gradually, over days, weeks, or months, but Sophia’s body could heal itself rapidly; she had never yet suffered an injury so severe it hadn’t healed beyond trace within minutes.

Furthermore, seeing the difference every night between what she ate and what her parents ate, exemplified once in a while by the blood spilled across chopped vegetables, Sophia knew another major way she was set apart. Sophia could eat food, but gained no nourishment from it and often instead found her body’s false parallel to digestion to be quite discomfiting. Preparing food, cooking it, even chewing and tasting it, could be quite sensual and enjoyable for her, but just as she experienced the food in supernatural detail before swallowing, she continued to experience it all the way from being swallowed to being expelled. It wasn’t until Sophia was almost eleven years old that she realized living people were not so minutely aware of their body’s internal workings, and after several months of trying to express in detail the way she experienced digestion she finally convinced her parents to stop expecting her to eat food with them at every meal.

Alternatively, Sophia had learned online that if her parents had tried to drink human blood -the only thing which could nourish her- they would likely become quite ill. They all still cooked together and took meals together, but for over six years Sophia had been drinking only blood while her parents ate their food. At one point Sophia had written an essay, for an English assignment her mother had given her, which analyzed the anti-vampire bias inherent in the way the word ‘food’ itself was used to the exclusion of human blood. The idea that what nourishes the living is all called ‘food’ while what nourishes vampires is not included in such a blanket term is just the sort of built-in bias toward humanity-as-baseline which gave Sophia insights into the more subtle differences between herself and others.

It was usually the less subtle differences Sophia noticed directly. She was able to lift a ton of solid stone while strong men could only lift dozens of pounds at a time. She was able able to leap high enough and far enough that living people took minutes or longer to catch up with her. She was fast enough, both in covering distance and in performing detailed tasks, that other people described her as a blur and she was frequently asked to perform tasks which would have been tedious and time-consuming for the living but which she could work through in a tiny fraction of the time.

Sophia was certainly aware that many of the ways she had to restrain herself, by moving more cautiously and significantly slower than she expected she was able, were due to problems the people around her had never considered. Sophia had quickly determined the maximum velocity at which she ought to collate papers, not just because of the violent winds generated by her rapid movements which could be countered with heavy paper weights, but also because above a certain speed the friction of paper on paper and sometimes of the papers with the air itself was enough to start fires and destroy all her work. Her strength was more than sufficient to crush or otherwise accidentally destroy things the people around her had certainly not considered to be fragile. Sophia had found that, even with so few places to go, people still expected travel between two points to take a certain, usually fairly specific, amount of time; the spare minutes she was afforded by people’s expectations, often standing near doorways in silence, had added up to many long hours of contemplation over the years.

Then there was her age; Sophia had been frozen, physically, in the body of a seven year old girl. Her parents had tried to minimize the effect of this by keeping her isolated from normally-aging people, and by keeping her with other seven and eight year olds in her rare, late-night Sunday School sessions; it had been effective, for a while. Since adults don’t change quickly and she was prevented from maintaining friendships with any children who were constantly growing up, Sophia was nearly a teenager before she began to be frustrated by her unchanging body. Unlike her success at altering the ritual of their family mealtime, Sophia was never able to convince her parents that she should be allowed to attend Sunday School with other children her actual age, or even to begin to be socially promoted with any particular class; they were convinced it would be too difficult for the other children to handle having a classmate who didn’t fit in than it would be for Sophia to cope with being treated only as old as she appeared to be. The argument that the outside world would only ever see her as a seven year old girl was never a convincing one for Sophia; she wondered why her church couldn’t be the ones to set a better example for the world.

Finally, there was the big thing about vampires which was about to change Sophia’s life more significantly than anything since the last time it had turned her world upside-down; vampire blood and organs had radically altered the face of modern medicine. Sophia had been a recipient of vampire-enhanced healthcare when a childhood illness began destroying her body from the inside out, though it had been too early in the history of vampires working openly with the living to be able to save her life. She had been donating her blood into the system twice weekly since she’d been turned, knowing it had been used throughout the region to enhance emergency-room care, paramedic care, and other forms of recovery. In a few nights, Sophia would begin donating her organs as well, saving the lives of children with her child-sized organs in ways the adult-sized organs of physically-mature vampires had been unable to do for her. Sophia sometimes felt her life was defined by extreme medical interventions, beginning with trying to save her first life and now in her freely giving of her second life to try to save others.

In the nearly-sixteen years since vampires had first revealed their existence to the world, and especially in the decade since Sophia herself had been turned, the daily miracles made possible by widespread use of vampire blood and vampire organs had become commonplace and even expected in the public eye. When Sophia was too young to really comprehend, every life saved had been reported on and celebrated in the media. The first successful vampire-to-human organ transplant had been a big deal. The first vampire lung transplant had received live coverage, and the first transplant of each other major organ seemed to get equal time. The first vampire limb used to make an amputee whole had been talked about for weeks, and the sports press couldn’t stop talking about the quadruple amputee now playing ball at a professional level, thanks to the donations of a well-matched vampire. A particularly well-endowed vampire whose generous donations had altered the face of pornography got a few seconds of jokes on every channel, but it was when a vampire’s organs were proven capable of reversing reproductive failures up to and including radical hysterectomies that the news anchors figured out how to speak maturely about such delicate procedures. The first children born from couples whose reproductive organs had been replaced or restored by vampire-enhanced healthcare had proven to share their parents’ genes, and reporting on their total normalcy -no signs of dhampyrs among them- was one of the few aspects of the new reality of modern healthcare which continued to be newsworthy. When the first of the new generation of child vampires like Sophia began to reach the legal age of consent in 2012, most news outlets picked up a story or two about how children in need of transplants were finally being brought into the new, better world of vampire-enhanced healthcare.

Sophia herself did not expect her donations to get any coverage at all; it was 2017, and the world had moved on. The big medical stories were no longer in treating the debilitatingly sick, but in medical advancements which might soon be able to prevent illnesses from reaching the point of organ failure, the need for hospitalization, or any major intervention. Sophia’s donations would be saving lives and improving the quality of people’s lives, but they weren’t newsworthy. Her ability to recover from a major organ donation, to regrow whole organs or limbs, was probably the biggest thing beyond her theoretical immortality which set her apart from the living, but even that significant a difference was now considered part of the baseline; if not for humans individually, then for humanity collectively.